Review: The story behind the singalong holiday classic that shall reign forever and ever

Published in Books News

When I was a teenager in Tennessee during the 1980s, Christmas officially launched the day after Thanksgiving: holly wreaths hung on front doors, shoppers thronging local malls. My father busied himself in the kitchen, assembling tins of Chex mix and pecan-freckled cheeseballs, gifts for friends in our Baptist congregation. On Christmas Eve, we felt a frisson as the choir rose in the sanctuary’s loft, belting out George Frideric Handel’s “Hallelujah Chorus,” a centerpiece of their Advent repertoire.

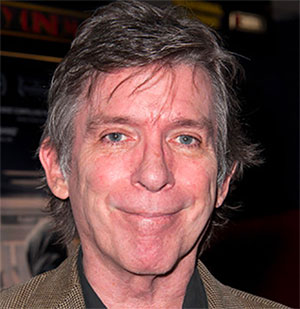

Georgetown University academic Charles King evokes the sacred upswell of the “Hallelujah Chorus” and other songs in his spirited, pitch-perfect “Every Valley,” the story behind the creation of the composer’s “Messiah.”

In the early 18th century, Baroque music tapped Italian structures, such as operas and arias, while innovating with orchestras, dissonances and tempo. A handsome prodigy from Saxony, Handel (1685-1759) was broad-shouldered and feisty, famed for sarcastic asides.

After training in Germany and Italy, he fell under the spell of London, newly emerged from decades of political strife. In 1723, with financial support and the imprimatur of King George I, he settled into a Mayfair townhouse, his residence for the rest of his life, composing opera seria (“serious opera”).

King showcases eccentric Charles Jennens, a melancholic Leicestershire squire who used his immense wealth to acquire paintings and build a formidable library. He also played harpsichord competently. Intrigued by ancient biblical texts, he filled notebooks with verses lifted from the King James translation.

“Jennens had selected passages from Isaiah and the minor prophets, then from the Gospels and the book of Revelation ... at every turn it would have been impossible to miss the connections between the cosmic and contemporary,” King observes. “A light would shine on those who walked in darkness. A lame man would leap like a deer. A just government would at last rule the land.”

These conceits became the underpinnings for Handel’s oratorio and a collaboration that enervated and frustrated both men.

“Every Valley” beautifully captures the dynamic that seeded the masterpiece. Jennens aimed for a bold narrative of a sacrificial savior, from annunciation through resurrection. (Indeed, “Messiah” debuted in Dublin the week of Easter, 1742.)

Handel’s status was tied up with the fortunes of the royal family as its members jockeyed for power. King fleshes out his cast with an adulterous alto, a displaced African prince and acerbic satirist Jonathan Swift, unearthing a strange yet enticing history of what-ifs and who-could-have-knowns? The author finds analogues for our own tempestuous era; his Grub Street chapter reminds us that the chatter in Hanoverian Britain was not so distant from today’s Facebook and Instagram.

“Another artery of publishers, coffee houses, and tenements — Grub Street — became a byword for the urge to share one’s views and, even more, the ache to have someone notice,” he writes. “People of varying social classes found themselves swept up in the first great age of stressing over likes and followers and then, when all else failed, turning to the obscene.”

As King notes, Handel’s “Messiah” was the crescendo of a resplendent career; it doesn’t quite resemble anything else in the composer’s oeuvre. By weaving the strands together, King enlarges a work that never ceases to stir us, “a confection of spiraling solos and soaring choruses ... a relevant, grown-up way of engaging with the present.”

____

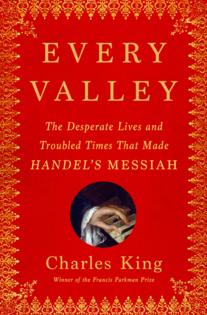

Every Valley: The Desperate Lives and Troubled Times That Made Handel’s Messiah

By: Charles King.

Publisher: Doubleday, 352 pages, $32.

©2024 The Minnesota Star Tribune. Visit at startribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments