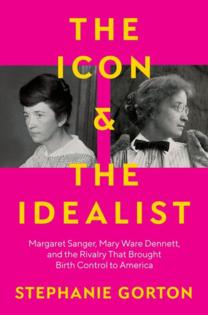

Review: Soap opera-worthy book traces how a century-old feud over birth control affects us to this day

Published in Books News

Hey, writer-director-producer Ryan Murphy, if you’re looking for subjects for future installments of TV’s “Feud” franchise, look no further: The clash between turn-of-the-last-century birth control activists Margaret Sanger and Mary Ware Dennett may be just the ticket.

Not interesting enough, you say? Au contraire, Ryan Murphy. Stephanie Gorton documents them in “The Icon and the Idealist: Margaret Sanger, Mary Ware Dennett, and the Rivalry That Brought Birth Control to America.” The pair not only dedicated themselves to bringing relief to women doomed to give birth annually (mostly able-bodied white women, of course, thanks to a little thing called eugenics that came to sully both women’s efforts) but they also led unconventional lives.

Did you know that Sanger divorced her first husband, carried on several affairs, including one with “The War of the Worlds” author H.G. Wells, and then raised eyebrows when she married much-older oil magnate James Noah Henry Slee, whom she generally ignored over the course of their life together? “He seems a nice man,” a friend wrote to her after the wedding, “and deserves a more suitable wife.”

Although not as well known as Sanger, Dennett isn’t to be outdone, Ryan Murphy. As Gorton recounts, Dennett divorced a husband, too, after he left her to live with a married couple. She kept custody of their two sons, unusual at the time, and the exes battled over them until the boys reached adulthood. Dennett also flirted with an affair, but remained unmarried. And she was an artist of some renown, dabbling with guadameciles, items made out of tooled leather that she exhibited and sold. Actor Marlene Dietrich bought a pair of Dennett-made bookends.

As you can see, Ryan Murphy, Sanger and Dennett would be of interest, regardless, but their feud over the best way to mainstream birth control is the real drama. Gorton does an exemplary job of keeping straight the various leagues and committees — it was an era of “associations galore,” she writes — that the two were members of or that they created. Both were involved with the National Birth Control League at one point, but Sanger broke with it over a slight that sparked the end of what had been a cordial relationship with Dennett. Sanger eventually started the American Birth Control League, with others to follow; Dennett, the Voluntary Parenthood League.

Really, Ryan Murphy, you need to pick up a copy of Gorton’s book because you will be as fascinated as I was with how she teases out compelling details about the times the women lived in and how their efforts were affected. For instance, the Depression may have been the single most important event in the birth control movement, even more so than women getting the right to vote, because Congress and the public were more moved by the economic argument for fewer babies than the humanitarian one. Having to support “relief babies” was a nonstarter.

Gorton is equally adept at plumbing Sanger’s and Dennett’s personalities, thus the “icon” and the “idealist” of the title, and how the paths they followed contributed to successes and failures. Had they been able to put their differences aside and collaborate, who knows what would have happened or how that would have been passed down to us?

Even though birth control is now available to almost all, arguments about it and bodily autonomy still rage. And the Comstock Act, which criminalizes mailing some birth control materials, remains a threat.

OK, Ryan Murphy, the ball is in your court.

____

The Icon and the Idealist

By: Stephanie Gorton.

Publisher: Ecco, 458 pages, $32.

©2024 The Minnesota Star Tribune. Visit at startribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments