Current News

/ArcaMax

California Senate greenlights energy reform bills as Democrats pursue “affordability”

After falling short last year, lawmakers in the state Senate are advancing a flurry of bills intended to give customers relief from ever-rising electricity bills and rein in investor-owned utilities like PG&E, which is raking in record profits. The plans are central to the promise of Gov. Gavin Newsom and top Democrats to make California more ...Read more

Citi Bike agrees to curb e-bike speeds at 15 mph after service suspension threat from NYC Mayor Eric Adams admin

NEW YORK — Citi Bike has agreed to curb the speed at which its e-bikes can go at 15 miles per hour — a move that came in response to a service suspension threat from Mayor Eric Adams’ administration.

The electric Citi Bikes can currently ride at 18 miles per hour, a limit the service’s operator, Lyft, previously set as part of an ...Read more

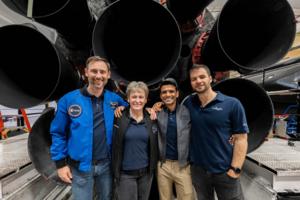

Axiom Space's record-setter to lead astronauts from 3 nations on private mission

Peggy Whitson has spent nearly two years of her life in space as an Axiom Space employee and former NASA astronaut.

Next week she’ll lead a mission with three men representing countries that haven’t sent anyone to space in more than four decades.

Whitson, 65, will command the Ax-4 mission targeting liftoff as early as 8:22 a.m. Tuesday ...Read more

Sacramento County cuts funding for Sheriff's Office during budget hearing

SACRAMENTO, Califs. — Public safety was at the center of budget discussions Wednesday as the Sacramento County Board of Supervisors unanimously approved the county’s recommended $8.9 billion budget.

With a full chamber, the daylong meeting ended with cuts to Sacramento County Sheriff’s Office and the addition of a principal criminal ...Read more

Maryland state trooper sentenced to 6 years for soliciting bribes from alleged drug dealer

BALTIMORE — A Maryland State Police trooper was sentenced Thursday to six years in federal prison after he admitted to passing information to a suspect in a drug case in exchange for cash.

The sentence came after Justin Riggs, 35, pleaded guilty to drug and bribery charges, signing an agreement where the former corporal admitted to telling ...Read more

Social media, text chains helped anti-ICE protesters get the word out during Minneapolis raid

MINNEAPOLIS — As word spread Tuesday about a large law enforcement presence involving immigration officers in south Minneapolis, a crowd of around 200 residents flooded the area.

City council members and activists drew attention to the scene on social media. Organizers tapped networks of trained legal observers. Concerned neighbors walked ...Read more

Netherlands to vote on October 29 after government falls

The Netherlands will hold a general election on October 29 after far-right leader Geert Wilders pulled his Freedom Party out of the Dutch government earlier this week.

The Minister of the Interior Judith Uitermark posted the date on X Friday.

Wilders pulled the plug on the coalition after his partners rejected his latest proposals to curb ...Read more

Russia hits Kyiv with missile wave after Putin vowed reprisals

Russian drone and missile attacks killed at least three people in Kyiv and wounded more than a dozen others, in a wave of overnight strikes including civilian targets that followed President Vladimir Putin’s vow to retaliate for a Ukrainian drone attack on Russian air bases.

Tymur Tkachenko, head of Kyiv military administration, posted the ...Read more

State moves to suspend licenses of troubled LA nursing home companies

LOS ANGELES — The California Department of Public Health is moving to suspend the licenses of seven Southern California nursing facilities that have been repeatedly cited in recent years for contributing to patients' deaths.

The state health department sent letters last month to seven companies in Los Angeles County that received at least two...Read more

GirlsDoPorn boss, once 1 of FBI's 10 most wanted, pleads guilty to sex trafficking

LOS ANGELES — After three years on the run and a stint on the FBI's Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list, the leader of GirlsDoPorn, Michael Pratt, pleaded guilty to sex trafficking charges in San Diego on Thursday, authorities said.

Pratt used force, fraud and coercion to recruit hundreds of women, many of whom were in their late teens, to ...Read more

Former LA County sheriff's oversight official faces retaliation investigation

LOS ANGELES — The former chairman of the Los Angeles County Sheriff Civilian Oversight Commission is under investigation for alleged retaliation against a Sheriff's Department sergeant who faced scrutiny for his role in a unit accused of pursuing politically motivated cases.

Sean Kennedy, a Loyola Law School professor who resigned from the ...Read more

Lethal algae bloom is over, but sickened marine mammals aren't safe yet

LOS ANGELES — It was one of the largest, longest and most lethal harmful algae blooms in Southern California's recorded history, claiming the lives of hundreds of dolphins and sea lions between Baja California and the Central Coast. And now, finally, it's over.

Levels of toxic algae species in Southern California coastal waters have declined ...Read more

'Unfortunately, Altadena is for sale': Developers are buying up burned lots

LOS ANGELES — In the wake of the devastating Eaton fire that tore through Altadena in January, hundreds of signs sprouted up in the ash-laden yards of burned-down homes: "Altadena Not for Sale."

The slogan signified a resistance toward outside investors looking to buy up the droves of suddenly buildable lots. But as the summer real estate ...Read more

Who tinkered with a Georgia county border? Line moved behind a powerful sheriff's house

HOMER, Ga. — There’s a mystery in Sheriff Billy Carlton Speed’s backyard.

Somehow, the border between two rural Georgia counties abruptly moved behind Speed’s house a few years ago, a curved line that puts his residence in Banks County, where he’s the chief lawman, rather than in Franklin County, where he’s not.

The shifting ...Read more

Duke University to offer more buyouts, anticipates layoffs under funding threats

In a video message Thursday, Duke University President Vincent Price said the private Durham school will offer new faculty buyouts ahead of likely staff layoffs in response to multiple federal funding threats under the Trump administration.

“We will, for the foreseeable future, have to be smaller — and do our work with fewer people,” ...Read more

Mayor Cherelle Parker and Philly Council reach $6.8 billion deal for the next city budget

After two days of nearly around-the-clock negotiations, Philadelphia City Council members on Thursday afternoon gave preliminary approval to a $6.8 billion city budget and almost all of the legislative proposals related to Mayor Cherelle L. Parker’s signature housing plan.

In the end, lawmakers green-lit wage and business tax cuts proposed by...Read more

Everyone from Jon Stewart to Alex Jones is weighing in on the Trump/Musk feud

Social media exploded with hot takes from all over the political spectrum Thursday amid the very public and acrimonious split between President Donald Trump and Elon Musk.

The feud between one of the world’s most powerful leaders and the world’s wealthiest man appeared to be simmering even before Musk left the White House last week after ...Read more

Michelle Obama shares her honest thoughts on Malia dropping last name

Former first lady Michelle Obama has opened up on her honest reaction to her eldest daughter, Malia, deciding to drop her last name.

Now going by Malia Ann, the former first daughter has adopted her middle name for her professional pursuits in Hollywood.

The new moniker appears in the credits of “The Heart,” the short film she wrote and ...Read more

Musk walks back threat to decommission SpaceX Dragon spacecraft

WASHINGTON — Elon Musk seemingly backed down from a threat to decommission SpaceX’s Dragon spacecraft that ferries cargo and people to the International Space Station for the U.S., made during an escalation of a spat between the billionaire and President Donald Trump.

SpaceX’s Dragon spacecraft is the company’s primary vehicle for ...Read more

'Confusion and frustration': Trump travel ban is unclear on who can visit the US

MIAMI — A day after President Donald Trump proclaimed full or partial travel restrictions for Haiti, Cuba, Venezuela and 16 other countries, U.S. tourist-visa holders from the targeted nations lacked clarity about whether they will be allowed into the United States when the ban is in force Monday.

The confusion stems from language the White ...Read more

Popular Stories

- Everyone from Jon Stewart to Alex Jones is weighing in on the Trump/Musk feud

- 'Unfortunately, Altadena is for sale': Developers are buying up burned lots

- Michelle Obama shares her honest thoughts on Malia dropping last name

- Duke University to offer more buyouts, anticipates layoffs under funding threats

- Musk walks back threat to decommission SpaceX Dragon spacecraft