Warning of ‘oligarchy,’ Biden channels Andrew Jackson

Published in News & Features

In some circumstances, a president’s official Farewell Address to the Nation may be an occasion for sunny reflection. President Joe Biden’s, delivered five days before he left office, began that way, with a celebration of America’s promise and of its progress under his tenure.

But midway through, Biden’s tone shifted abruptly, as he warned of a “dangerous concentration of power in the hands of a very few ultra-wealthy people, and the dangerous consequences if their abuse of power is left unchecked.”

In striking phrases, Biden charged that an “oligarchy” of “extreme wealth, power and influence” threatened not only Americans’ cherished legacy of equal opportunity, but their “basic rights and freedoms” and even the health of democracy itself. “We see the consequences all across America,” he observed. “And we’ve seen it before.”

Indeed. As historical grounding for his critique of today’s “tech-industrial complex,” Biden invoked President Dwight Eisenhower’s famous warning of a “military-industrial complex” in his 1961 Farewell Address. Reaching further back, Biden recalled the battle more than a century ago to tame the country’s industrial “robber barons.”

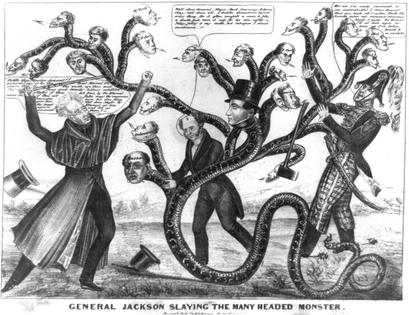

Yet, as scholars of American history well know, the roots of Biden’s rhetoric go back further still, to yet another president and another official Farewell Address: that of Andrew Jackson in 1837.

The resemblances between the two addresses are striking, especially given the nearly two centuries that separate them. Like Biden, Jackson began in fatherly tones, basking in Americans’ accomplishments and prosperity, before turning to warn of the force that threatened them.

That force was a “moneyed interest” embodied in a “multitude of corporations with exclusive privileges,” especially banks, whose concentrated wealth and influence gave them power over working people’s livelihoods and well-being, their rights, and their voice in government.

Jackson warned that if ordinary Americans dropped their guard, they would find “that the most important powers of government have been given or bartered away, and the control over your dearest interests has passed into the hands of these corporations.”

Biden’s warning of “the concentration of technology, power, and wealth” in self-interested private hands echoed this theme precisely.

Addressing the nation, both Jackson and Biden took pains to explain that they were not criticizing wealth itself. In his 1832 veto of the Bank of the United States recharter – the signature policy statement of his administration – Jackson had applauded American opportunity and the rewards that “superior industry, economy, and virtue” might bring. The danger lay not in wealth alone, but in the control that wealth gave some over others.

“It is to be regretted,” Jackson had then said, “that the rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes.” Every man had a right to the fruits of his own labor – as Biden would later put it, the right to “a fair shot, an even playing field, going as far as your hard work and talent can take you.”

Hence no one, said Jackson, should decry the riches that some men earned for themselves. But when the laws went beyond that, working “to make the rich richer and the potent more powerful,” then “the humble members of society” had “a right to complain of the injustice of their Government.”

Jackson’s words in his Bank Veto and Farewell Address pioneered what became a recurring theme in American political discourse.

A parting benediction is no place for party sniping, and Biden’s invocation of Eisenhower, a Republican, offered a gesture toward bipartisanship. His mention of the robber barons recalled another Republican president, Theodore Roosevelt, who famously busted trusts and decried what he called “malefactors of great wealth.”

Yet historically it has most often been Democrats who cast themselves as champions of the underdog, the little guy, the common man – what Jackson’s Farewell Address called “the agricultural, the mechanical, and the laboring classes … the bone and sinew of the country,” against “the rich and powerful.” Echoing Jackson, Democrats from William Jennings Bryan to Franklin Roosevelt to Sen. Elizabeth Warren have targeted big banks as wielders of illicit power and oppressors of the working people.

Recent shifts in society have muted this long-standing Democratic critique of concentrated wealth. Biden’s resuscitation of the old theme, while updating it to address new concerns – climate change, artificial intelligence, the spread of disinformation and of political dark money – represents a return to a recurring trope in American political discourse, and to a foundational identity for Biden’s Democratic Party.

Americans have been likening Andrew Jackson to Donald Trump ever since Trump himself proclaimed Jackson as his presidential model during his 2016 campaign. Trump has invoked Jacksonian precedents for his assertive foreign policy and his assault on the governing establishment, while critics have likened his immigration policy, and what they perceive as its racist underpinnings, to Jackson’s Native American removal and pro-slavery stances.

How much real resemblance Trump bears to Jackson, in either policy or personality, can be debated. But it is beyond doubt that, in warning of the threat of concentrated and unbridled power in the hands of a wealthy and privileged elite, Biden has recalled and reclaimed a Democratic Party heritage that traces back through Lyndon Johnson and Franklin Roosevelt to Woodrow Wilson, William Jennings Bryan – and finally to the party’s founder, Andrew Jackson.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Daniel Feller, University of Tennessee

Read more:

Trump’s executive orders can make change – but are limited and can be undone by the courts

Trump’s idea to use military to deport over 10 million migrants faces legal, constitutional and practical hurdles

Tariffs are back in the spotlight, but skepticism of free trade has deep roots in American history

Daniel Feller does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments