California is failing to meet its disability employment goal. State workers say they know why

Published in News & Features

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — Two decades ago, California set an ambitious employment goal: To reflect the state’s diverse population, one sixth of the government’s workforce would be filled by people with disabilities.

For years the state fell short of this objective, established by the State Personnel Board — and since the pandemic, California has moved further from that 16.6% benchmark.

Of the 116 departments the state reported employment metrics for, only 22% met the disabled worker goal as of September. Agencies that fall below an even lower disabled employment level of 13.3% are required to set hiring goals for the next year. This past year, 69 departments failed to meet that threshold.

The state’s hiring process, difficulty attaining telework accommodations and, in some departments, a culture that discourages employees from revealing hidden disabilities are to blame, former workers and groups representing disabled employees say.

“The state of California has set goals for itself and they talk about wanting to be a model employer and representing the demographics of the state,” said Paula Tobler, a supervising attorney with Disability Rights California. “And yet their percentages are going lower.”

Between 2017 and 2023, there was a 40% decrease in the public employment rate of disabled workers in the state, according to an analysis by Tobler’s organization.

The state says it’s improving. Last year, 88 departments experienced a net decrease in the number of workers with disabilities. In 2024, only 18 departments saw such decreases.

“The public has this perception that it’s very difficult to get a state job. We would like to be able to change that,” said the Department of Human Resources’ Chief Deputy Director Monica Erickson. She said for people with disabilities, the process may seem more daunting.

Despite this, Erickson said the state is attracting more applicants with disabilities in 2024 than it did in 2021. She pointed to updates made to employment exams as one example the state is trying to reduce barriers. She also said the human resources department has provided other state agencies with policies that make state employment more accessible to people with disabilities.

“I would say 100% the state is absolutely invested in this,” Erickson said. “The 16.6 number is certainly a goal to attain, but there’s nothing that says that we can’t go beyond that.”

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ data on the U.S. population, there were 3.9 million more people over the age of 15 identified as having a disability in 2024, compared to the average in 2020.

The pandemic resulted in more disabilities, but the state’s hiring practices haven’t adapted to the new reality, Tobler said.

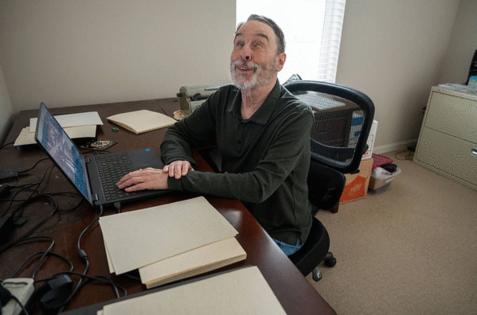

Scott Richmond, the former president of the Association of California State Employees with Disabilities, a membership group that advocates for workers, said at the state there’s a real reluctance on the part of a lot of people to share that they have a disability with their supervisors.

“They feel that they’re going to suffer in their jobs or careers if they reveal that they have a disability,” Richmond said.

Hiding to get along

Californians with disabilities are less represented in the general workforce. According to the Public Policy Institute of California, 62% of California adults without a disability are fully employed, while 30% of people with a disability work full time.

To its credit, the state employs more disabled workers compared to the private sector in California. According to the state’s most recent civil service census, conducted using 2022 numbers, 7.7% of the public workforce had a disability, compared to 4.7% of the general workforce. The state reported the rate of disabled workers in civil service had increased to 8% this June. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 27% of Californians have some disability in 2022.

The exact rate of disabled employment at California state government has fluctuated in recent years, but it has notably decreased since the COVID-19 pandemic.

Every year, the state collects demographic data for each department and tracks agencies’ progress on reaching the 16.6% goal. Of the departments which CalHR tracks, more than three quarters were below the target threshold. The human resources department then works with those agencies to develop a plan on how they can hire and retain disabled workers.

If there is a systemic problem with a department, Erickson said, CalHR tries to determine the root cause — for example, a hiring barrier or the job classification — and address it.

“If we’re focusing just on the departments that aren’t meeting compliance, that’s where the team will reach out to them and kind of find out what’s going on and ask them to put plans in place on how they’re going to meet these parity goals,” Erickson said.

CalHR provides struggling departments with best practices on how to attract and keep workers belonging to this protected class, she said.

“They talk to them one on one, they provide consultation services, they provide them with templates and tools, policies, all of those things get them to increase their parity number,” she said.

The decline in the disabled population of civil servants is due, in part, to the retirement of those employees and the state replacing them with people without disabilities, said Richmond, who is blind and worked at the state for over two decades, primarily as an analyst and manager with the Department of Health Care Services.

Richmond said disabled employees working for the state often feel unwelcome in some government workplaces.

“They don’t feel like the state is a place that embraces their disabilities, so they feel like, ‘Well I’ve got to hide this in order to get along,’” Richmond said. He said it’s difficult to fight that, if that’s the way people feel.

To address this issue, Richmond said there should be a consistent message from the governor’s office to agency heads: “It’s okay to be open about your disability, your rights will be safeguarded and protected.”

Richmond pointed to the State Compensation Insurance Fund as one of the departments that has fostered an inclusive work environment for disabled individuals. The department employs nearly 4,000 workers, a quarter of whom have a disability. As of September, 25 departments reported at least 16.6% of their staff has a disability.

Other departments, such as the California Correctional Health Care Services and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, fell well below the metric. The state excludes selected safety classes from its analysis.

Erickson said she’s empathetic to workers’ fear of discrimination and affirmed the state’s follows non-discriminatory employment practices.

To gauge the success of the state’s hiring and retention practices, CalHR collects data about workers’ change in disability status through a secure, online survey. Both CalHR and Richmond assured workers that only statistical data is shared with other state agencies.

The confidential survey results are used to ensure California is complying with state and federal labor statistic requirements. CalHR said the survey helps the state gauge the success of its hiring and retention rates for employees with disabilities.

“It is also used to identify barriers in employment practices and develop strategies to increase the representation of individuals with disabilities in state civil service. These efforts aim to create a more inclusive and equitable workforce,” the department said in a statement.

An alternative hiring process

The path to a more diverse public workforce begins with hiring more disabled employees. To achieve that, the state is tweaking part of the hiring process that prospective employees must navigate: the employment exam.

In the 1980s, the state recognized the exam could be a barrier to some prospective state workers with disabilities. California developed an alternative testing program for applicants with a disability known as the Limited Examination and Appointment Program. LEAP exams allow employees to demonstrate skills through on-the-job testing instead of a formal exam, or through the standard, non-LEAP process.

CalHR said courses offered through the state’s Equal Employment Opportunity Office about the LEAP process have improved recruitment efforts of disabled applicants in recent years. Between 2021 and 2024, the percentage of applicants who identified as having a disability increased from 8.5% to 8.9%.

Erickson said the marginal increase was evidence that more LEAP exams and better trained EEO officers had reduced hiring barriers to civil service. Disability advocates like Richmond say there are still gaps between certifying LEAP-eligible individuals and securing a job offer, which have partly prevented California from reaching its employment goal.

Erickson said one hiring improvement has been to target applicants with disabilities by advertising open positions that are well suited to LEAP candidates. CalHR regularly updates the LEAP exams when standard assessment are changed to ensure this accommodation is as widely available as possible, Erickson said.

“The more LEAP exams we have, the more eligible people with disabilities can take those exams, and as a result, hopefully get a job,” Erickson said.

Richmond agreed CalHR has devoted significant resources to developing alternative tests for the LEAP process, which hundreds of employees have benefited from in recent years.

One concern with the alternative testing program, Tobler noted, is that by participating in the LEAP process, applicants are exposing themselves to potential discrimination.

Tobler said it’s immediately clear in the hiring process if someone is a LEAP candidate. If that manager harbors biases about disabled workers, it could impact an individual’s chance of getting a job.

“That has left a bad taste in the mouth of people with disabilities,” Tobler said. She emphasized the need to end the stigma of disabled workers as “charity cases.”

She pointed to a report by the consulting firm Accenture which found that companies that offered disability programs and prioritized inclusive practices were more productive and earned more revenue than industry peers.

“Look at the data and see that actually people with disabilities are more often than not value added, not value taken away,” Tobler said.

Requesting to work remote

While the pandemic presented heightened dangers for people with disabilities, remote work proved to be a benefit for some who needed certain working conditions for health reasons.

When state employees were called back into the office earlier this year, some disabled workers requested reasonable accommodations in the form of continued telework. Some hoped the exemption to the return-to-office directive would prevent them from catching COVID-19, others knew that working from home provided more flexibility to meet their health needs.

In instances when those requests were denied, workers often chose to resign instead of putting their health at risk. It’s unclear how many employees resigned. CalHR said it does not track the reason people leave state service.

Departments handle reasonable accommodation requests internally, CalHR said. Without a statewide policy for processing these requests, departments deal with the requests differently.

CalHR proposed a model policy on reasonable accommodations that provides details on how departments can reject those requests due to undue hardship, which means the cost or disruptive nature of the accommodation is deemed too great by personnel administrators. The model policy also suggests different modifications departments can make to benefit employees, like assistive technologies and telework.

The state said 97% of departments have a reasonable accommodation policy. Some, but not all, departments have adopted the model policy, though CalHR has not tracked how many.

Tobler said accommodation requests can take a long time to process. She hears from workers whose telework requests have been denied by their departments due to insufficient doctor’s notes or HR managers blocking the accommodation, despite a worker’s supervisor approving it.

Tobler emphasized work from home requests are not attempts by some workers to get preferential treatment. Telework for workers with certain disabilities is a necessity to successfully do their jobs, she said.

She noted that some workers with non-visible disabilities don’t want to ask for an accommodation because “there’s a price to be paid to be identified as someone with disabilities.”

“In order to even ask for an accommodation … you have to live with whatever they think about you,” Tobler said. “I wish we lived in the world where that didn’t matter, but we do not live in that world.”

____

©2025 The Sacramento Bee. Visit at sacbee.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments