How nostalgia led to the invention of the first Christmas card

Published in News & Features

It’s a common seasonal refrain: “Christmas just isn’t like it used to be.”

This is not a new complaint. History shows that Christmas traditions are just as subject to change as any other aspect of human societies, and when customs change, there are always some who wish they could turn back the clock.

In the 1830s, the English solicitor William Sandys compiled a host of examples of Britons bemoaning the transformation of Christmas customs from earlier eras. Sandys himself was especially concerned about the decline of public caroling, noting the practice appeared “to get more neglected every year.” He worried that this “neglect” was indicative of a wider British tendency to observe Christmas with less “hospitality and innocent revelry” in the 19th century than in the past.

Yet the 19th century also produced new holiday customs. In fact, many of the new Christmas practices in Sandy’s time went on to become established traditions themselves – and are now the subject of nostalgia and fretted over by those who fear their decline. Take, for example, the humble Christmas card. My research shows that these printed seasonal greetings borrowed from the customs of the past to move Christmas into a new age.

Annual sales and circulation of Christmas cards have been in decline since the 1990s. Laments over the potential “death” of the Christmas card have been especially vocal in the United Kingdom, where the mailing of Christmas greetings to family and friends via printed cards was long considered to be an essential element of a “British Christmas.”

Indeed, historians Martin Johnes and Mark Connelly both argue that throughout the 20th century the Christmas card was viewed as just as essential a part of Britain’s distinctive blend of holiday traditions as children hanging stockings at the end of their beds, Christmas pantomimes, and the eating of turkey and Brussels sprouts.

Yet, as these same historians are quick to note, at one time Britons did none of these things at Christmas. Each of these traditions became an element of the customary British Christmas only during the second half of the 19th century and the early decades of the 20th.

This makes them all relatively new additions to the country’s holiday customs, especially when viewed in light of Christmas’ more than 2,000-year history.

The custom of mailing printed Christmas cards began in the middle decades of the 19th century and was a product of the industrial revolution. It was made affordable by new innovations in printing and papermaking and more efficient modes of transportation such as the railway.

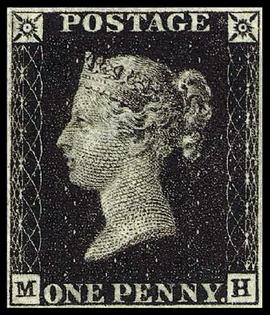

The development of this new tradition was also facilitated by Parliament’s introduction of the Penny Post in 1840, which allowed Britons to mail letters to any address in the United Kingdom for the small price of a penny stamp.

Most historians date the Christmas card’s arrival to 1843, the same year in which Charles Dickens published “A Christmas Carol.”

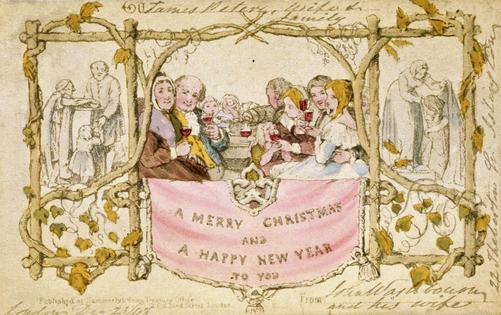

In that year, the inventor and civil servant Henry Cole commissioned the artist John Callcott Horsley to design a card to help Cole handle his Christmas correspondence more efficiently.

Printed versions of Cole’s card were also made available for sale, but the high price of one shilling apiece left them outside the bounds of affordability for most of the Victorian population.

Cole’s experiment, however, inspired other printers to produce similar but more affordable Christmas cards. The use of these cheaper cards began to spread in the 1850s and had established itself as a holiday tradition by the final decades of the century.

While the Christmas card may have seemed like an entirely new invention to Victorian senders and receivers, the first Christmas card’s design was actually influenced by other, older British holiday traditions.

As historians Timothy Larsen and the late Neil Armstrong have demonstrated, Christmas’ status as an established holiday meant that new Christmas customs developed during the 19th century needed to connect with, supplement or replace already existing traditions. The Christmas card was no exception to this recorded pattern.

In 1843, many Britons bemoaned the disappearance of a variety of “Old English” Christmas customs. Foremost among these were traditions of Christmas “hospitality,” including Christmas and New Year’s visiting, when family, friends and neighbors went to each other’s homes to drink toasts and offer best wishes for the holiday and the coming year.

Scholars argue popular belief in these traditions depended on a mixture of recalled reality and constructed fictions. Foremost among the latter were the popular stories depicting “old English hospitality” at Christmas by the American writer Washington Irving, published in the 1820s. In fact, Britons regularly invoked Irving’s accounts of Christmas at the fictional country house, Bracebridge Hall, when debating the changing character of their nation’s Christmas observances.

Regardless of these “old” customs’ historical reality, they nevertheless came to feature prominently in discussions regarding the supposed disappearance of a range of community level Christmas observances, including feasting, caroling and public acts of charity.

All of these, it was believed, were endangered in an increasingly urban Britain characterized by class tensions, heightened population mobility and mass anonymity.

While it is unclear whether these ongoing debates inspired Cole’s decision to commission his 1843 Christmas card, the illustration Horsley designed for him alluded to them directly.

The card features a family framed by trestles adorned with holly and mistletoe, accompanied on either side by charitable scenes involving the feeding and clothing of the poor. The center of the card – and the symbolic center of Horsley’s Christmas vision – however, is the family of three clearly defined generations enjoying a collective feast, including the classic English Christmas pudding.

They face the viewer, their glasses raised in a toast, directly above a banner wishing them a “A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year.” The central visual imagery of the card – as a “paper visitor” to the home of the recipient – replicates the social act of toasting associated with the older custom of holiday visits.

In fact, Horsley’s design invoked many of the same elements featured in Irving’s stories. This is not surprising, given that in later life Horsley recalled the impact of reading Irving’s depictions of the “Christmas at Bracebridge Hall” as a boy, and how he and his sister Fanny had been “determined to do our best to keep Christmas in such a notable fashion.”

Early Christmas cards favored similar imagery associated with the “Old English” Christmas of carolers, acts of charity, the playing of country sports, games such as blindman’s bluff, copious greenery, feasting and the toasting of Christmas and the New Year.

These Christmas cards were thus novel, industrial products adorned with the imagery of British Christmases past.

The development, and ultimate triumph, of the Christmas card in Victorian Britain demonstrates how nostalgia was channeled into invention. The Christmas card did not revitalize the traditions of Christmas and New Year’s visiting; it offered a paper replacement for them.

Industrial production and transportation transformed the physical visitor into a paper proxy, allowing more people to visit many more of the homes of others during the holiday season than they ever would have been able to in person.

The desire to hold on to one element of an older, supposedly declining Christmas tradition thus proved instrumental in helping to create a new holiday tradition in the midst of unprecedented changes in the character of communications and social relations.

Today, a similar context of social and technological changes has caused some to predict the “death” of the Christmas card. The history of the 19th century suggests, however, that should the tradition die, whatever replaces it will thrive by drawing selectively on the Christmas customs of the past.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Christopher Ferguson, Auburn University

Read more:

Why does red wine cause headaches? Our research points to a compound found in the grapes’ skin

Here’s why Christmas movies are so appealing this holiday season

How the Christmas pudding, with ingredients taken from the colonies, became an iconic British food

Christopher Ferguson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments