Current News

/ArcaMax

US health, tech officials to launch data-sharing plan

Top Trump administration health officials are expected to bring tech companies to the White House this week to roll out a plan to encourage more seamless sharing of health care data, according to people familiar with the matter.

Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services ...Read more

Royal Caribbean crew member stabs colleague, jumps overboard. He's found dead

MIAMI — A Royal Caribbean crew member stabbed a colleague on board during a cruise this week, Bahamian police say, then jumped into the waters off the island chain. He was found dead.

The 35-year-old South African male stabbed a 28-year-old fellow crew member “multiple times,” the Royal Bahamas Police said in a July 25 statement. The ...Read more

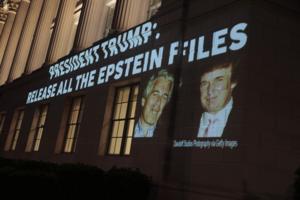

Maryland Democrats urge Trump to release Jeffrey Epstein files

As the Jeffrey Epstein files continue to dominate headlines in Washington, Maryland Democrats are hoping to seize an opportunity to ramp up pressure on President Donald Trump.

This week, three of the state’s House members joined dozens of their colleagues on both sides of the aisle in sponsoring legislation related to Epstein, the disgraced ...Read more

Trump calls Thai, Cambodian leaders in bid to end conflict

U.S. President Donald Trump said he called the leaders of Thailand and Cambodia to urge them to stop the fighting that erupted earlier this week, warning he wouldn’t make a trade deal with either country while the conflict continued.

“We happen to be, by coincidence, currently dealing on Trade with both Countries, but do not want to make ...Read more

EU-US trade agreement now hinges mostly on Trump's verdict

After months of intensive talks and shuttle diplomacy, a trade agreement between the European Union and the U.S. now rests mostly on Donald Trump.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen will travel to Scotland to meet the U.S. president on Sunday, as the two sides aim to conclude a deal ahead of Friday’s deadline, at which point ...Read more

18-year-old arrested in UNM shooting that killed 14-year-old boy

An 18-year-old suspect has been arrested in a shooting at a University of New Mexico dormitory that left a 14-year-old boy dead and wounded a 19-year-old early Friday morning, authorities said.

The incident involved four individuals who were reportedly playing video games in a dorm room at Casas del Rio, a privately owned on‑campus housing ...Read more

Gwyneth Paltrow stars as Astronomer spokesperson after Coldplay kiss-cam scandal

NEW YORK — Astronomer has enlisted Gwyneth Paltrow as their temporary spokesperson after her ex-husband and Coldplay frontman Chris Martin caught the company’s CEO and head of human resources cuddling at his concert.

In a video shared on social media Friday night, Paltrow, seated behind a desk with her hands clasped, reveals she’d been ...Read more

New details about police activity after lawmaker shootings raise questions about response

MINNEAPOLIS — From the first 911 call, moments after Minnesota state Sen. John Hoffman and his wife, Yvette, were shot at their home in the early morning of June 14, police knew a masked gunman was impersonating an officer, had targeted a politician and was on the move.

Yet it would take 10 hours for law enforcement to systematically alert ...Read more

Taiwan opposition defeats recall, keeps legislative control

Taiwan’s opposition will keep its legislative majority in a blow to President Lai Ching-te’s Democratic Progressive Party, with voters overwhelmingly rejecting an attempt to recall 24 Kuomintang lawmakers.

Voters in every targeted constituency rebuffed the recall effort, according to Central Election Commission data as of 8:45 p.m., with ...Read more

Trump calls Thai, Cambodian leaders in bid to end conflict

President Donald Trump said he called the leaders of Thailand and Cambodia to urge them to stop the fighting that erupted earlier this week, warning he wouldn’t make a trade deal with either country while the conflict continued.

“We happen to be, by coincidence, currently dealing on Trade with both Countries, but do not want to make any ...Read more

Seeking the elusive path for immigrants to legally come to US: 'People are dying in line'

LOS ANGELES — John Manley is sick of people telling immigrants to "stand in line" and "do it the right way."

An immigration attorney for almost three decades in Los Angeles, he said what most don't understand is that trying to legally come into the United States is nearly impossible for people from certain nations like Mexico.

"People are ...Read more

Giant pandas, tiger attacks and the ugly fight to control the San Francisco Zoo

Molting peacocks squawked in the distance and a Pacific breeze whispered through the eucalyptus as flamingo keeper Liz Gibbons tidied her station at the San Francisco Zoo.

It had been an unusually cold summer in a city famous for them. Marooned on "a breathtaking piece of land" at the peninsula's far western edge, steps from the deadly surf at ...Read more

Florida allowed capture of threatened giant manta ray for overseas aquarium

ORLANDO, Fla. — Denis Richard watched five men heave a giant manta ray from the waters off Panama City Beach and plop it into a pool on their boat deck.

“Let him go,” he yelled. “You ought to be ashamed of yourselves.”

Richard, a dolphin tour boat operator, was outraged that a threatened species often called the “angel of the sea�...Read more

California Democrats may target GOP congressional districts to counter Texas

LOS ANGELES — California Democrats led by Gov. Gavin Newsom may upend the state's mandate for independently drawn political districts as part of a brewing, national political brawl over the balance of power in Congress and the fate of the aggressive, right-wing agenda of President Donald Trump and the GOP.

The effort being considered by state...Read more

They are still discovering bodies in Altadena 6 months after fire. Are there other victims?

LOS ANGELES — While Katherine Alcantara was evacuating from her smoke-filled west Altadena home during January's firestorm, she remembered seeing her longtime neighbor returning home across the street.

In the chaos, she assumed he had come back to rescue his pets and grab some important belongings before heading to safety.

She never imagined...Read more

Anwar's broken promises spark protests demanding his ouster

KUALA LUMPUR, Malaysia — When Anwar Ibrahim came to power in late 2022, it was with the promise of reform: cleaner government, a leaner budget and a break from the patronage politics that had defined his predecessors.

Nearly three years later, not much of that has happened. His plans for targeted subsidies and reduced public spending have ...Read more

RFK Jr. to oust advisory panel on cancer screenings, report says

Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. plans to oust members of the advisory board that decides which preventive health measures are covered by insurance, The Wall Street Journal reported Friday.

Kennedy is expected to remove the 16 members of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force because he views them as “woke,” the ...Read more

One of the grenades recovered ahead of blast that killed 3 LA deputies is missing, authorities say

LOS ANGELES — One of the two hand grenades found in a Santa Monica townhome complex ahead of the deadly blast that killed three Los Angeles County sheriff’s detectives is currently missing, authorities said Friday.

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives has determined that one of the two grenades detonated on July 18, “...Read more

News briefs

Trump picks Alina Habba to continue running New Jersey's US Attorney’s Office

WASHINGTON — President Donald Trump selected Alina Habba to continue running the U.S. Attorney’s Office in New Jersey on a temporary basis, the latest twist in a succession drama after federal judges had picked her top assistant to take her place.

Trump chose ...Read more

Police records in Idaho murder case: 5 things revealed about Bryan Kohberger

BOISE, Idaho — Hundreds of pages of documents released Wednesday by the Moscow Police Department after Bryan Kohberger’s sentencing hearing revealed some new information about the man who murdered four University of Idaho students.

Not much has been known about the personality of Kohberger, who sat through his plea hearing and sentencing ...Read more

Popular Stories

- A funeral home gave parents an unmarked box with their son's brain in it, lawsuit says

- Seeking the elusive path for immigrants to legally come to US: 'People are dying in line'

- Giant pandas, tiger attacks and the ugly fight to control the San Francisco Zoo

- 9-year-old dies after incident at Hersheypark's waterpark in Pa.

- Florida allowed capture of threatened giant manta ray for overseas aquarium