Hurricane Milton's forecast track was stunningly accurate. The next one may not be as exact

Published in News & Features

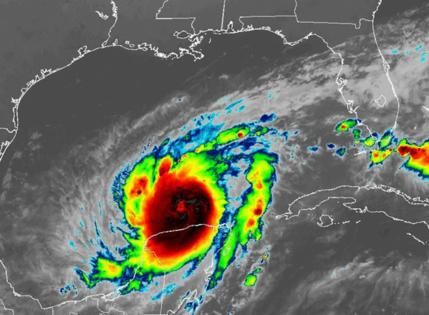

FORT LAUDERDALE, Fla. — A stunningly precise forecast of Hurricane Milton’s track gave Floridians a strong head start to prepare this past week. It marked the latest instance that a major hurricane has been mapped in precise detail — its path was accurately predicted a whole four days before it made landfall.

Milton’s first cone forecast came out on Saturday morning, Oct. 5. The center of the cone put a bull’s-eye on Sarasota. Four days later, Milton made landfall just about 4 miles south, on Siesta Key.

Similarly, forecasts for Hurricane Helene formed before the system even had a name, and they were right on target, as the storm made landfall on Sept. 26 in the Big Bend area of the Florida Gulf Coast.

The accuracy of hurricane forecasts has improved through the years, and the recent forecasts for Helene and Milton were notably accurate. Yet, there’s no guarantee that all forecasts will be so precise — given the chaotic nature of hurricanes, and the minute changes that can have massive impacts on land.

"We got Helene right; Beryl was pretty close,” said Craig Setzer, a meteorologist and hurricane preparedness specialist. “This one was a pretty good track forecast. But you never really know until it’s over.”

Milton’s path toward Florida

During Milton’s four days of traveling across the Gulf, there was a persistent, anxiety-inducing wiggle to the storm’s path.

One day the centerline traveled over St. Petersburg and Tampa Bay, the next it was back down at Sarasota, then back up to St. Petersburg, then Sarasota. Each shift struck fear or relief, depending on the projected location.

That fear was based on the fact that the leading right-hand quadrant of a hurricane is the “dirty” side, where the winds are strongest, and push the most water. If Tampa was south of the eye, that dirty side would shoot water into the funnel-shaped bay, resulting in a forecasted 15 feet of storm surge.

To put that wiggle in perspective, St. Petersburg and Sarasota are 40 or 50 miles apart. The storm was traveling from 500 miles away, and not in a straight path — forecasters had to anticipate a turn to the left (northeast) at some point, and then a turn east to shore.

And to clarify, the National Hurricane Center instructs the public to consider the entire cone as a probable path of the eye of the storm. It’s difficult for many to not focus on the centerline, though.

Regardless of those wiggles, the forecast was startlingly accurate.

Gaining strength very quickly

When Milton was a mere tropical system, it loitered in the bottom horseshoe of the Gulf, west of the Yucatan Peninsula, and became more organized.

Setzer said that when he woke up the morning of Oct. 5 and looked at satellite imagery, he immediately thought, “This is going to be a problem,” because it was getting organized so quickly.

The high that was holding it in place eased, and Milton took off east. Forecasters knew a trough would eventually turn it northeast toward Florida. They also projected, because Gulf waters were so hot and wind shear so absent, that the storm would vault to monstrous Category 5 strength, then oscillate between Category 4 and 5 before hitting wind shear close to shore and weakening again. All these changes put residents on high alert across the state.

As a result, the state urged millions of people to leave Florida’s western coast, triggering one of the biggest evacuations in the state’s history.

“This was all predicted, but you don’t know exactly how sharp the turn is going to be, or when it’s going to take place. The Hurricane Center did a great job with all those things,” Setzer said.

The path accuracy came in part from understanding the timing of a big low-pressure trough to the north. “There was a trough that was swinging down across the southern U.S. and into the Gulf,” said Luke Culver, of the National Weather Service, “and that was what picked up Milton and brought it northeast, into the Gulf Coast.”

Five days out, the National Hurricane Center’s modeling deciphered when the trough would intersect Milton, and how that would change the storm’s trajectory.

“Obviously the timing of that, when the trough grabbed Milton and how fast Milton was moving, was really what determined how far north or south it was going to make landfall,” Culver said.

Jeff Berardelli, chief meteorologist and climate specialist at WFLA-TV in Tampa Bay, said that as the storm traveled northeast, all the forecast models showed an eventual turn to the east, into shore.

“Our challenge was to figure out which models were more accurate with the timing of the eastward turn. If it happened too late, the storm would have gone right to Tampa Bay and it would have been a worst-case scenario, with 15 feet of surge in Tampa and St. Pete. But either way it was going to be a bad scenario for someone.”

Berardelli said that the consensus of the models showed a track just south of Tampa Bay. “That gave us a little more confidence,” he said.

“This was a testament to the fact that our models really are getting better,” Setzer said.

Still, the little 50-mile wiggle made a world of difference to densely populated Tampa Bay, which didn’t want to be on the southern, or “dirty” right side of the storm.

Setzer said it was great track forecast. But with Tampa Bay’s dense population, and the shape of the bay, a 50-mile shift in the track could produce minimal storm surge, or massive storm surge, with hundreds of thousands of homes impacted.

“The difference of those 50 miles couldn’t have been more stark,” he said.

Why all the nerve-racking wobbles?

Small wobbles are always happening as a hurricane travels, but once there’s a big human population in the bull’s-eye, people start to notice the minute changes, Setzer said.

“The wobbles happen because a hurricane is not completely vertically stacked,” he said, “or it could be tilted a little bit by some wind shear, or sometimes we have smaller spins inside of a larger circulation.

“As that inside cog is spinning around a bigger wheel, it pulls that bigger wheel left and right, so little wobbles are very common. But as they get close to the coast they make a huge difference to people’s lives.”

Berardelli made his forecasts from Tampa as those wobbles happened.

“When you’re taking about a hair making such a big difference, it’s a nerve-racking forecast,” he said. “But no matter where this storm went, someone was going to see disastrous consequences.”

©2024 South Florida Sun Sentinel. Visit at sun-sentinel.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments