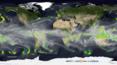

Atmospheric rivers are shifting poleward, reshaping global weather patterns

Published in News & Features

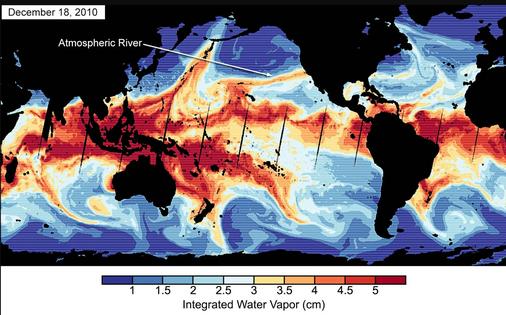

Atmospheric rivers – those long, narrow bands of water vapor in the sky that bring heavy rain and storms to the U.S. West Coast and many other regions – are shifting toward higher latitudes, and that’s changing weather patterns around the world.

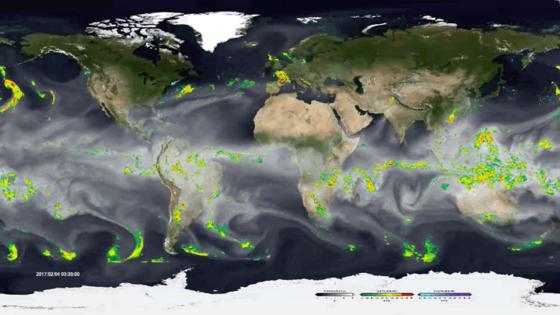

The shift is worsening droughts in some regions, intensifying flooding in others, and putting water resources that many communities rely on at risk. When atmospheric rivers reach far northward into the Arctic, they can also melt sea ice, affecting the global climate.

In a new study published in Science Advances, University of California, Santa Barbara, climate scientist Qinghua Ding and I show that atmospheric rivers have shifted about 6 to 10 degrees toward the two poles over the past four decades.

Atmospheric rivers aren’t just a U.S West Coast thing. They form in many parts of the world and provide over half of the mean annual runoff in these regions, including the U.S. Southeast coasts and West Coast, Southeast Asia, New Zealand, northern Spain, Portugal, the United Kingdom and south-central Chile.

California relies on atmospheric rivers for up to 50% of its yearly rainfall. A series of winter atmospheric rivers there can bring enough rain and snow to end a drought, as parts of the region saw in 2023.

While atmospheric rivers share a similar origin – moisture supply from the tropics – atmospheric instability of the jet stream allows them to curve poleward in different ways. No two atmospheric rivers are exactly alike.

What particularly interests climate scientists, including us, is the collective behavior of atmospheric rivers. Atmospheric rivers are commonly seen in the extratropics, a region between the latitudes of 30 and 50 degrees in both hemispheres that includes most of the continental U.S., southern Australia and Chile.

Our study shows that atmospheric rivers have been shifting poleward over the past four decades. In both hemispheres, activity has increased along 50 degrees north and 50 degrees south, while it has decreased along 30 degrees north and 30 degrees south since 1979. In North America, that means more atmospheric rivers drenching British Columbia and Alaska.

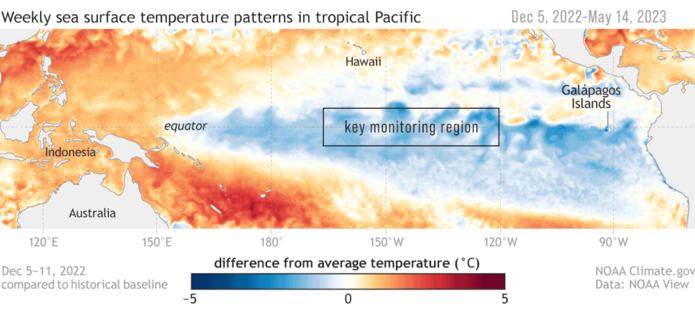

One main reason for this shift is changes in sea surface temperatures in the eastern tropical Pacific. Since 2000, waters in the eastern tropical Pacific have had a cooling tendency, which affects atmospheric circulation worldwide. This cooling, often associated with La Niña conditions, pushes atmospheric rivers toward the poles.

The poleward movement of atmospheric rivers can be explained as a chain of interconnected processes.

During La Niña conditions, when sea surface temperatures cool in the eastern tropical Pacific, the Walker circulation – giant loops of air that affect precipitation as they rise and fall over different parts of the tropics – strengthens over the western Pacific. This stronger circulation causes the tropical rainfall belt to expand. The expanded tropical rainfall, combined with changes in atmospheric eddy patterns, results in high-pressure anomalies and wind patterns that steer atmospheric rivers farther poleward.

Conversely, during El Niño conditions, with warmer sea surface temperatures, the mechanism operates in the opposite direction, shifting atmospheric rivers so they don’t travel as far from the equator.

The shifts raise important questions about how climate models predict future changes in atmospheric rivers. Current models might underestimate natural variability, such as changes in the tropical Pacific, which can significantly affect atmospheric rivers. Understanding this connection can help forecasters make better predictions about future rainfall patterns and water availability.

A shift in atmospheric rivers can have big effects on local climates.

In the subtropics, where atmospheric rivers are becoming less common, the result could be longer droughts and less water. Many areas, such as California and southern Brazil, depend on atmospheric rivers for rainfall to fill reservoirs and support farming. Without this moisture, these areas could face more water shortages, putting stress on communities, farms and ecosystems.

In higher latitudes, atmospheric rivers moving poleward could lead to more extreme rainfall, flooding and landslides in places such as the U.S. Pacific Northwest, Europe, and even in polar regions.

In the Arctic, more atmospheric rivers could speed up sea ice melting, adding to global warming and affecting animals that rely on the ice. An earlier study I was involved in found that the trend in summertime atmospheric river activity may contribute 36% of the increasing trend in summer moisture over the entire Arctic since 1979.

So far, the shifts we have seen still mainly reflect changes due to natural processes, but human-induced global warming also plays a role. Global warming is expected to increase the overall frequency and intensity of atmospheric rivers because a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture.

How that might change as the planet continues to warm is less clear. Predicting future changes remains uncertain due largely to the difficulty in predicting the natural swings between El Niño and La Niña, which play an important role in atmospheric river shifts.

As the world gets warmer, atmospheric rivers – and the critical rains they bring – will keep changing course. We need to understand and adapt to these changes so communities can keep thriving in a changing climate.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Zhe Li, University Corporation for Atmospheric Research

Read more:

What is an atmospheric river? With flooding and mudslides in California, a hydrologist explains the good and bad of these storms and how they’re changing

Atmospheric rivers are hitting the Arctic more often, and increasingly melting its sea ice

How California could save up its rain to ease future droughts — instead of watching epic atmospheric river rainfall drain into the Pacific

Zhe Li does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments