Intoxication nation: a double shot of US history

Published in News & Features

Uncommon Courses is an occasional series from The Conversation U.S. highlighting unconventional approaches to teaching.

“Intoxication Nation: Alcohol in American History”

I wanted to get students excited about studying the past by learning about something that is very much a part of their own lives.

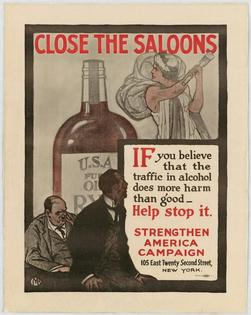

Alcohol – somewhat surprisingly to me at first – featured prominently in my own research on minority rights and U.S. democracy in the mid-19th century. As a result, I knew quite a bit about the temperance movement and conflicts over prohibition during that period. Designing this course allowed me to broaden my expertise.

Prohibition is a must-do subject. Students expect it. But I cover several hundred years of history: from the 17th-century invention of rum – as a byproduct of sugar produced by enslaved people – to the rise of craft beer and craft spirits in the 21st century.

Along the way, I’m thrilled when students get excited about details that allow them to taste a more complicated historical cocktail. For example, they learn why white women’s production of hard cider was crucial to the survival of colonial Virginia. The short answer: Potable water was in short supply, alcoholic drinks were far healthier, and white men – and their indentured and enslaved workforce – were busy raising tobacco. It fell to women to turn fruit into salvation.

Alcohol remains a big and almost inescapable part of American society. But of late, Americans have been drinking differently – and thinking about drinking differently.

Examples abound. Alcohol producers, we learn, now face competition from legalized weed. Drinking l evels rose during the COVID-19 pandemic, yet interest is declining among Gen Zers. The “wine mom” culture that brought some mothers together now faces mounting criticism.

And, of course, there’s the never-ending debate about the health benefits and risks of alcohol. Of late, the risks seem to be dominating headlines.

Alcohol has been a highly controversial, central aspect of the American experience, shaping virtually all sectors of our society – political and constitutional, business and economic, social and cultural.

Historian Bill Rorabaugh’s “The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition”: a classic social history explaining why Americans in the early 19th century drank twice as much per capita as we do today

Jack London’s alcoholic memoir, “John Barleycorn”: a deep dive into the notorious workingmen’s saloons of the industrial era, as well as one person’s reckoning with alcoholism

“Days of Wine and Roses”: the 1962 film starring Jack Lemmon and Lee Remick that spotlighted the place of alcoholic marriages and Alcoholics Anonymous in post-World War II America

Murray Sperber’s “Beer and Circus: How Big-Time College Sports is Crippling Undergraduate Education”: a provocative early 2000s assessment of college sports and the surrounding party culture vis-a-vis declining academic standards – still relevant today

Like any history course, this one aims to develop student’s analytical, written, research and verbal skills. In lots of ways, the topic is just a tool to get students to grow their brains. But I also seek to grow students’ critical awareness of the place of alcohol in their own lives. The course has also informed students’ paths after graduation – including some who wound up working in the alcohol industry or recovery organizations.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Kyle G. Volk, University of Montana

Read more:

Alcohol use disorder can be treated with an array of medications – but few people have heard of them

For some craft beer drinkers, less can mean more

Opioid overdose: A bioethicist explains why restricting supply may not be the right solution

Kyle G. Volk works for the Department of History at the University of Montana. He has received funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Comments