FDA’s new regulations underscore the complexity around screening for women with dense breasts

Published in News & Features

The Food and Drug Administration implemented a rule to go into effect on Sept. 10, 2024, requiring mammography facilities to notify women about their breast density. The goal is to ensure that women nationwide are informed about the risks of breast density, advised that other imaging tests might help find cancers and urged to talk with their doctors about next steps based on their individual situation.

The FDA originally issued the rule on March 10, 2023, but extended the implementation date to give mammography facilities additional time to adhere.

The Conversation U.S. asked a team of experts in social science and patients’ health behaviors, health policy, radiology and primary care and health services research to explain the FDA’s new regulations about these health communications and what women should consider as they decide whether to pursue additional imaging tests, often called supplemental screening.

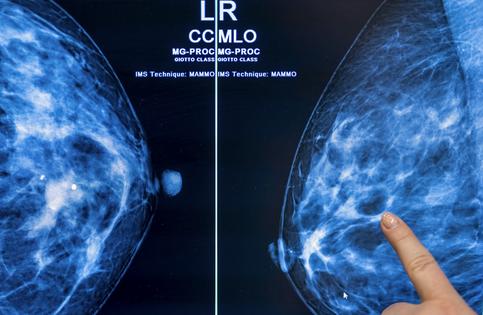

Breast density is categorized into four categories: fatty, scattered tissue, heterogeneously dense or extremely dense.

Dense breasts are composed of more fibrous, connective tissue and glandular tissue – meaning glands that produce milk and tubes that carry it to the nipple – than fatty tissue. Because fibroglandular tissue and breast masses both look white on mammographic images, greater breast density makes it more difficult to detect cancer. Nearly half of all American women are categorized as having dense breasts.

Having dense breasts also increases the risk of getting breast cancer, though the reason for this is unknown.

Because of this, decisions about breast cancer screening get more complicated. While evidence is clear that regular mammograms save lives, additional testing such as ultrasound, MRI or contrast-enhanced mammography may be warranted for women with dense breasts.

The FDA now requires specific language to ensure that all women receive the same “accurate, complete and understandable breast density information.” After a mammogram, women must be informed:

– Whether their breasts are dense or not dense

– That having dense breasts increases the risk of breast cancer

– That having dense breasts makes it harder to find breast cancer on mammograms

– That for those with dense breasts, additional imaging tests might help find cancer

They must also be advised to discuss their individual situation with their health care provider, to determine which, if any, additional screening might be indicated.

Prior to the federal rule, 38 U.S. states required some form of breast density notification. But some states had no notification requirements, and among the others there were many inconsistencies that raised concerns by advocates, including women with dense breasts whose advanced cancer had not been detected on a mammogram.

The FDA standardized the information women must receive. It is written at an eighth grade reading level and may address racial and literacy-level differences in women’s knowledge about breast density and reactions to written notifications.

For instance, our research team found disproportionately more confusion and anxiety among women of color, those with low literacy and women for whom English was not their first language. And some women with low literacy reported decreased future intentions to undergo mammographic screening.

Standard mammograms use X-rays to produce two-dimensional images of the breast. A newer type of mammography imaging called tomosynthesis produces 3D images, which find more cancers among women with dense breasts. So, researchers and doctors generally agree that women with dense breasts should undergo tomosynthesis screening when available.

There is still limited scientific evidence to guide recommendations for supplemental breast screening beyond standard mammography or tomosynthesis for women with dense breast tissue. Data shows that supplemental screening with ultrasound, MRI or contrast-enhanced mammography may detect additional cancers, but there are no prospective studies confirming that such additional screening saves more lives.

So far, there is no data from randomized clinical trials showing that supplemental breast MRIs, the most often-recommended supplemental screening, reduce death from breast cancer.

However, more early stage – but not late-stage – cancers are found with MRIs, which may require less extensive surgery and less chemotherapy.

Various professional organizations and experts interpret the available data about supplemental screening differently, arriving at different conclusions and recommendations. An important consideration is the woman’s individual level of risk, since emerging evidence suggests that women whose personal risk of developing breast cancer is high are most likely to benefit from supplemental screening.

Some organizations have concluded that current evidence is too limited to make a recommendation for supplemental screening, or they do not recommend routine use of supplemental screening for women based solely on breast density. Others recommend additional screening for women with extremely or heterogeneously dense breasts, even when their risk is at the intermediate level.

Because personal risk of breast cancer is a crucial consideration in deciding whether to undergo supplemental screening, women should understand their own risk.

The American College of Radiology recommends that all women undergo risk assessment by age 25. Women and their providers can use risk calculators such as Tyrer-Cuzick, which is free and available online.

Women should also understand that breast density is only one of several risks for breast cancer, and some of the others can be modified. Engaging in regular physical activity, maintaining a healthy weight, limiting alcohol use and eating a healthy diet rich in vegetables can all decrease breast cancer risk.

Amid the debate about the benefits of supplemental breast screening, there is less discussion about its possible harms. Most common are false alarms: results that suggest a finding of cancer that require follow-up testing. Less commonly, a biopsy is needed, which may lead to short-term fear and anxiety, medical bills or potential complications from interventions.

Supplemental screening can also lead to overdiagnosis and overtreatment – the small risk of identifying and treating a cancer that would have never posed a problem.

MRI screening also involves use of a chemical substance called gadolinium to improve imaging. Although tiny amounts of gadolinium are retained in the body, the FDA considers the contrast agent to be safe when given to patients with normal kidney function.

MRIs may also identify incidental findings outside the breast – such as in the lungs – that warrant additional concern, testing and cost. Women should consider their tolerance for such risks, relative to their desire for the benefits of additional screening.

The out-of-pocket cost of additional screening beyond a mammogram is also a consideration; only 29 states plus the District of Columbia require insurance coverage for supplemental breast cancer screening, and only three states – New York, Connecticut and Illinois – mandate insurance coverage with no copays.

Though the FDA urges women to talk with their providers, our research found that few women have such conversations and that many providers lack sufficient knowledge about breast density and current guidelines for breast screening.

It’s not yet clear why, but providers receive little or no training about breast density and report little confidence in their ability to counsel patients on this topic.

To address this knowledge deficit in some health care settings, radiologists, whose screening guidelines are more stringent than some other organizations, sometimes provide a recommendation for supplemental screening as part of their mammography report to the provider who ordered the mammogram.

Learning more about the topic in advance of a discussion with a provider can help a woman better understand her options.

Numerous online resources can provide more information, including the American Cancer Society, the website Dense Breast-info and the American College of Radiology.

Armed with information about the complexities of breast density and its impact on breast cancer screening, women can discuss their personal risk with their providers and evaluate the options for supplemental screening, with consideration of how they value the benefits and harms associated with different tests.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Nancy Kressin, Boston University; Christine M. Gunn, Dartmouth College; Priscilla J. Slanetz, Boston University, and Tracy A. Battaglia, Yale University

Read more:

Breast cancer awareness campaigns too often overlook those with metastatic breast cancer – here’s how they can do better

What links aging and disease? A growing body of research says it’s a faulty metabolism

The FDA’s rule change requiring providers to inform women about breast density could lead to a flurry of questions

Nancy Kressin received funding from The American Cancer Society.

Christine M. Gunn receives funding from National Cancer Institute (1K07CA221899).

Priscilla Slanetz is site Principal Investigator for the Tomosynthesis Mammographic Imaging Screening Trial (TMIST). She also serves on the Practice Parameter Committee of the American College of Radiology (ACR), is Chair of the ACR Commission of Publications and Lifelong Learning, and serves on the ACR Board of Chancellors and the Association of Academic Radiology's Board of Directors and Research & Education Fund. Finally, she is co-author on the ACR Appropriateness Criteria Supplemental Breast Cancer Screening Based on Breast Density document which was first published in November 2021 and will be updated in late fall 2024.

Tracy A. Battaglia received grant funding from the American Cancer Society. She is co-author on the ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Supplemental Breast Cancer Screening Based on Breast Density published in 2021.

Comments