Current News

/ArcaMax

Black man assaulted by white nationalist group Patriot Front wins nearly $2.8 million in court

BOSTON — The Black man who was shoved and assaulted by a white nationalist group in downtown Boston on Fourth of July weekend won nearly $2.8 million in damages against the group, Patriot Front.

Charles Murrell III, a musician and teacher, sued Patriot Front in August 2023 in federal court. The lawsuit targeted both the group itself as well ...Read more

FEMA centers open amid anxiety over recovery from the Eaton, Palisades fires

Jared Robbins walked up to a row of FEMA trailers in Pasadena with a sheet of paper where he had written some of the most pressing questions about his situation after his Altadena home was burned by the Eaton fire less than a week ago.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency opened two disaster recovery centers Tuesday to assist people like ...Read more

NY Times, other newspapers ask federal judge to reject OpenAI, Microsoft challenges to copyright suit

NEW YORK — Lawyers for The New York Times, the Daily News and other newspapers Tuesday asked a Manhattan judge to reject an effort by OpenAI and Microsoft to dismiss parts of their lawsuits accusing the tech giants of stealing reporters’ stories to train their AI products.

The News, its affiliated newspapers in Media News Group and Tribune ...Read more

L.A. County to create fund for wildfire victims

As fire victims flood GoFundMe for help with rebuilding, the L.A. County government will create its own fund for residents who lost their livelihoods or whose homes or businesses were reduced to rubble by devastating wildfires.

The county Board of Supervisors, which met Tuesday for the first time since fires decimated large swaths of the county...Read more

LA fire officials could have put engines in Palisades before the fire broke out. They didn't

LOS ANGELES — As the Los Angeles Fire Department faced extraordinary warnings of life-threatening winds, top commanders decided not to assign for emergency deployment roughly 1,000 available firefighters and dozens of water-carrying engines in advance of the fire that destroyed much of the Pacific Palisades and continues to burn, interviews ...Read more

A week after LA firestorms began, the threat continues as the unprecedented losses sink in

LOS ANGELES — A week after flames leveled huge swaths of Pacific Palisades and Altadena, Southern California remained under a severe fire threat as residents still struggled to comprehend the scale of the loss.

An army of firefighters spent Tuesday putting out small fires before they got out of control, and continued building containment ...Read more

Biden creates 2 vast national monuments during final week in office

President Joe Biden on Tuesday created two new vast national monuments in California’s desert and far north that protect lands considered sacred by tribes, bolstering his conservation legacy days before leaving office.

Biden signed proclamations establishing the 624,000-acre Chuckwalla National Monument south of Joshua Tree National Park in ...Read more

$20 billion Delta tunnel plan wins endorsement from Silicon Valley's largest water agency

SAN JOSE, Calif. — Gov. Gavin Newsom’s $20 billion plan to build a massive, 45-mile long tunnel under the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta to make it easier to move water from Northern California to Southern California won the endorsement of Silicon Valley’s largest water agency on Tuesday.

By a vote of 6-1, with director Rebecca Eisenberg ...Read more

Gov. Hochul putting a cop on every subway train in NYC at night, installing more safety barriers

NEW YORK — Gov. Kathy Hochul said the state will be paying to put police on every overnight subway train in NYC for the next six months, “to reduce crime and the fear of crime” in the MTA’s mass transit system.

“I want to see more uniformed police officers,” Hochul said Tuesday in her annual State of the State address. “Not just ...Read more

Anchorage power outages extend to 3rd day in wake of 'extreme' warm January storm

ANCHORAGE, Alaska — Hundreds of Anchorage residents remained without power for a third day following a rare January storm that brought record warmth and hurricane-force winds over the weekend.

Chugach Electric Association said the extensive repairs necessitated by Sunday's storm means some members may not get power back until Wednesday.

The ...Read more

Defense nominee Hegseth sticks to script at his confirmation hearing

WASHINGTON — Pete Hegseth weathered repeated efforts by Democrats on the Senate Armed Services Committee to assail his lack of qualifications to lead the Pentagon on Tuesday, buoyed by praise from Republicans of President-elect Donald Trump’s “out-of-the-box” pick to serve as secretary of Defense.

Partisan lines of support and hostility...Read more

Scores of LA teachers lose homes; students from 2 burned-down LA schools to resume class

LOS ANGELES — Students from two burned-down Los Angeles elementary schools will resume classes Wednesday in new locations in neighborhoods near fire-ravaged Pacific Palisades as employee unions estimate that at least 150 district staff, including many teachers, have lost their homes.

Students who were attending Palisades Charter Elementary ...Read more

Virginia House advances constitutional amendments on reproductive and voting rights, same-sex marriage

RICHMOND, Va. — The Virginia House of Delegates passed three state constitutional amendments Tuesday that would enshrine in state law reproductive rights, same-sex marriage and automatic restoration of voting rights for people who had completed felony sentences.

It’s the first step in a two-year process led by Democrats to amend the state ...Read more

Elon Musk accused by SEC of bilking Twitter investors out of millions

WASHINGTON — Elon Musk cheated Twitter shareholders out of more than $150 million by waiting too long to disclose his growing stake in the company as he prepared a takeover bid, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission claimed in a lawsuit filed days before the Trump administration takes over.

The agency’s complaint, which was ...Read more

No Pride flags allowed: Idaho proposal would ban many displays in public school classrooms

BOISE, Idaho — Many flags for ideological causes would be banned in public schools under a proposed Idaho law, in addition to those for LGBTQ+ Pride and political parties.

Rep. Ted Hill, R-Eagle, introduced House Bill 10 on Tuesday to ban most flags in state-funded public classrooms.

Teachers could still display the U.S. flag, state flags, ...Read more

LA City Council moves to bar evictions for unauthorized people and pets amid fire emergency

LOS ANGELES — Los Angeles city officials are seeking to protect some tenants from eviction in the wake of the fires that have ravaged the region and destroyed thousands of homes.

In a 15 to 0 vote Tuesday, Los Angeles City Council members directed the city attorney to draft an ordinance that for a year would prevent evictions for having extra...Read more

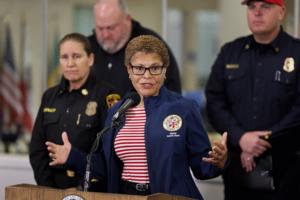

LA Mayor Karen Bass was at embassy cocktail party in Ghana as Palisades fire exploded

LOS ANGELES — Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass was at a cocktail party at the U.S. ambassador to Ghana's residence Jan. 7 as the Palisades fire exploded, pictures posted on social media show.

Bass was in Ghana as part of a Biden administration delegation to the inauguration of Ghanaian President John Dramani Mahama. A gathering for the delegation...Read more

News briefs

Idaho police could arrest immigrants without legal status in proposed law to mirror Texas

BOISE, Idaho — Immigrants living in Idaho without legal status could be arrested and charged by local law enforcement, according to a new proposed bill, giving local officials authority in an area that has historically been left to federal officials.

...Read more

What threats lurk in the smoke and ash of LA-area fires? New health warnings

LOS ANGELES — As Santa Ana wind conditions continue to stoke fears of resurgent wildfires across Los Angeles, health officials are warning of yet another wind-borne threat: ash and dust from active fire zones and burn scars.

On Tuesday, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health issued a windblown dust and ash advisory until 7 p.m. ...Read more

Gov. Hochul backs key public safety reforms favored by NYC mayor, but not bail reform, in NY State of the State address

NEW YORK — The public safety policies Gov. Hochul laid out in her State of the State speech Tuesday were likely music to New York City Mayor Eric Adams’ ears, as he has called on Albany to take up several of those proposals during this year’s legislative session.

That included Hochul’s vows to roll back some of the discovery reforms the...Read more

Popular Stories

- Here's what happens with TikTok if Supreme Court upholds ban

- San Diego Gas & Electric power outages hit 5,620 customers as Santa Ana winds pick up

- Trump tax cuts: What's at stake as House GOP, Dems debate extending signature plan

- Lori Daybell's Idaho case may offer path to dump death penalty in Kohberger murder trial

- What will happen to Donald Trump's New Jersey liquor licenses after his punishment-free sentencing in hush money case?