Current News

/ArcaMax

Harsh reality of US trade deal stirs EU soul-searching over lost clout

As European Union leaders work through the consequences of their new trading arrangement with the U.S., they are confronting the bitter reality of just how far they have fallen.

Donald Trump held court on Sunday at one of the golf courses he owns on the Scottish coast, touting the new ballroom he’d had built at the clubhouse and delivering a...Read more

A DACA recipient accidentally drove into Mexico. Now he's being fast-tracked for deportation

SAN DIEGO -- A rideshare driver allowed to live in the U.S. under a program for immigrants who arrived undocumented as children said that he mistakenly drove into Tijuana while transporting passengers near San Ysidro.

Now, Erick Alexander Hernández, a 34-year-old man originally from El Salvador, is in immigration custody in San Diego and being...Read more

Perseid meteor shower: When it peaks and what could spoil the party

LOS ANGELES -- When it comes to meteor showers, the Perseids pop. It's not just about the quantity of meteors (as many as 100 per hour) and their showy quality (fireballs!) but also their superb timing.

The annual shower hits its peak on warm, laid-back August nights as the Earth crosses paths with the dust cloud left by comet Swift-Tuttle on ...Read more

Israelis begin to question the morality of their war in Gaza

The news on Israel’s main TV channel had just finished a segment on how hunger in Gaza is portrayed around the world when the anchor looked up and said: “Maybe it’s finally time to acknowledge that this isn’t a public relations failure, but a moral one.”

Whether or not it was a Walter Cronkite moment, when the U.S. broadcaster ...Read more

Shane Tamura targeted NFL, suicide note blames CTE brain injury for NYC Park Ave. mass shooting

NEW YORK — Shane Tamura, the Park Avenue gunman who killed an NYPD officer and three others before taking his own life, left behind a suicide note saying he suffered from CTE, a brain injury often linked to playing football, and was targeting the NFL — but took the wrong elevator, officials said Tuesday.

Tamura, 27, who played competitive ...Read more

COVID rising in California. How bad will this summer be?

COVID-19 is once again on the rise in California.

It remains to be seen whether this latest uptick foreshadows the sort of misery seen last year — when the state was walloped by its worst summertime surge since 2022 — or proves fleeting. But officials and experts say it's nevertheless a reminder of the seasonal potency of the still-...Read more

Damaging, golf ball-size hail will fall more frequently because of climate change, researchers warn

During severe thunderstorms, rising air shoots icy pellets the size of Dippin’ Dots ice cream into the bitter cold of upper atmospheric layers. There, supercooled water freezes onto the small particles to form hail, which then falls when it gets too heavy for the storm’s upward draft.

As climate change warms average global temperatures, ...Read more

Republicans call Medicaid rife with fraudsters. This man sees no choice but to break the rules

MISSOULA, Mont. — As congressional Republicans finalized Medicaid work requirements in President Donald Trump’s budget bill, one man who relies on that government-subsidized health coverage was trying to coax his old car to start after an eight-hour shift making sandwiches.

James asked that only his middle name be used to tell his story so ...Read more

Americans may aspire to single-family homes, but in South Korea, apartments are king

SEOUL, South Korea — For many Americans, the apartment where 29-year-old IT specialist Lee Chang-hee lives might be the stuff of nightmares.

Located just outside the capital of Seoul, the building isn't very tall — just 16 stories — by South Korean standards, but the complex consists of 36 separate structures, which are nearly identical ...Read more

Medicaid cuts are likely to worsen mental health care in rural America

Across the nation, Medicaid is the single largest payer for mental health care, and in rural America, residents disproportionately rely on the public insurance program.

But Medicaid cuts in the massive tax and spending bill signed into law earlier this month will worsen mental health disparities in those communities, experts say, as patients ...Read more

'Tired of forcing children to duck and cover,' Gov. JB Pritzker signs two more gun control measures

With gun violence still a persistent problem despite recent drops in Chicago, Gov. JB Pritzker signed a pair of gun control efforts into law Monday — one that requires Illinoisans to more quickly report lost firearms and another mandating law enforcement agencies statewide participate in a federal gun tracing platform.

The two modest measures...Read more

5 dead, including NYPD officer, in shooting at Park Avenue skyscraper housing Blackstone Group and NFL headquarters

NEW YORK — A police officer and three other people were killed after a gunman opened fire Monday evening at a Midtown Manhattan office building that houses The Blackstone Group and NFL headquarters, police said.

The “lone shooter” was later “neutralized,” NYPD Commissioner Jessica Tisch said. Police sources said the man shot and ...Read more

Trump weighs whether to let Taiwan leader transit through US

The Trump administration is debating whether to allow a planned U.S. stopover by Taiwan’s leader next week as concerns mount that it could derail trade talks with China and a potential summit with President Xi Jinping, according to people familiar with the matter.

Taiwanese President Lai Ching-te was planning to stop in New York on Aug. 4 ...Read more

Philippines' Marcos pushes more social programs, jobs to soothe public discontent

Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. said recent midterm elections showed the public’s discontent over issues ranging from poverty to corruption, pledging to roll out more social programs, create jobs and attract investment in the second half of his single six-year term.

“If only data will be the basis, the economy is doing well. ...Read more

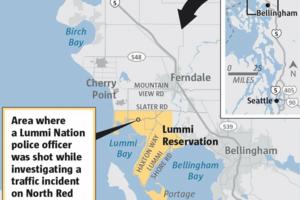

Lummi Nation police officer shot multiple times; suspect arrested

SEATTLE — A Lummi Nation police officer was shot multiple times early Monday, according to the Whatcom County sheriff’s office.

The suspected shooter was arrested Monday afternoon, Lummi Nation reported in a news release.

The 37-year-old officer had responded at 12:52 a.m. to a vehicle that had driven off the road into a ditch in the 3200 ...Read more

Trump to resume Thailand, Cambodia trade talks after truce

President Donald Trump said the U.S. will resume trade negotiations with Thailand and Cambodia after they agreed to halt clashes along their disputed border, taking credit for pushing them to peace after threatening punishing tariffs.

The two Southeast Asian nations reached a ceasefire Tuesday after five days of fighting, including airstrikes ...Read more

Three dead, 10 injured in Turks and Caicos; premier blames Haitian gangs

A night of partying out in the Turks and Caicos Islands turned deadly over the weekend when three people were killed and 10 others were wounded in a mass shooting spree in the sun-soaked tourist destination.

The island-chain’s first mass shooting, the incident unfolded at 2:57 a.m. Sunday when officers with the Royal Turks and Caicos Islands ...Read more

Chokeholds, bikers and 'roving patrols': Are Trump's ICE tactics legal?

An appellate court appears poised to side with the federal judge who blocked immigration agents from conducting "roving patrols" and snatching people off the streets of Southern California, likely setting up another Supreme Court showdown.

Arguments in the case were held Monday before a three-judge panel of the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals...Read more

DHS: 140,000 Minnesotans could lose health insurance under federal tax cut and spending package

Close to 140,000 Minnesotans are likely to lose health care coverage under Medicaid cuts that are expected to cost the state $1.4 billion in federal revenue over the next four years, according to a new analysis from state health officials.

The Minnesota Department of Human Services released updated projections Monday of the impact the federal ...Read more

NYPD officer, 2 civilians shot at Park Avenue skyscraper housing Blackstone Group, NFL offices

NEW YORK — A police officer and two civilians were shot Monday evening at a Midtown Manhattan office building that houses The Blackstone Group and NFL headquarters by “a lone shooter” who was later “neutralized,” NYPD Commissioner Jessica Tisch said.

The shooting happened at 345 Park Ave. and 51st Street around 6:30 p.m., when police ...Read more

Popular Stories

- Republicans call Medicaid rife with fraudsters. This man sees no choice but to break the rules

- COVID rising in California. How bad will this summer be?

- 5 dead, including NYPD officer, in shooting at Park Avenue skyscraper housing Blackstone Group and NFL headquarters

- Trump weighs whether to let Taiwan leader transit through US

- 'Tired of forcing children to duck and cover,' Gov. JB Pritzker signs two more gun control measures