One year ago, Pope Francis disavowed the ‘Doctrine of Discovery’ – but Indigenous Catholics’ work for respect and recognition goes back decades

Published in News & Features

It has been more than 500 years since Vatican decrees gave European colonizers permission to carve up the “New World” – and just one since Pope Francis disavowed them.

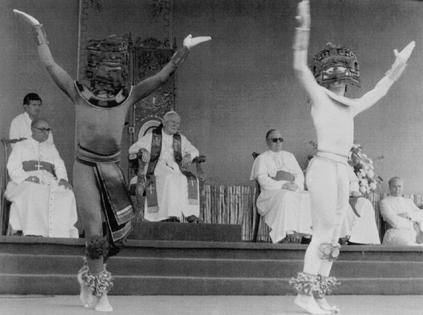

On March 30, 2023, Francis repudiated the “Doctrine of Discovery”: a set of ideas the Spanish and Portuguese, in particular, used to justify seizing land they had “discovered” and colonizing Indigenous people in the the land they came to call the Americas. The Vatican’s statement not only rejected the doctrine, but also apologized for historical atrocities carried out by Christians and affirmed the rights and cultural values of Indigenous peoples.

The repudiation can hardly undo centuries of oppressing Indigenous people and stealing their lands. Yet the statement is monumental in ways that signal cultural and political shifts within the Catholic Church. It recognized decades of work by Indigenous Catholics to demand that their very own church respect their history, culture and faith – a focus of my work as a historian of Mexico and religion.

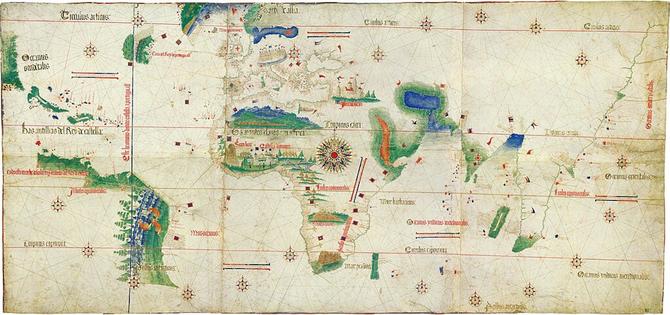

The Doctrine of Discovery has its roots in 15th century papal documents, called “papal bulls,” which were issued amid Spain’s and Portugal’s colonial expansion in Africa and the recently “discovered” Americas.

“Inter Caetera,” for example, which was issued in 1493, drew a line 100 leagues, or around 350 miles, to the west of the Azores and Cape Verde in the Atlantic Ocean. The document declared that all lands west of that line were free to be discovered, colonized and Christianized by the Kingdoms of Castile and León – modern-day Spain.

In other words, the Catholic Church gave Spain a monopoly on the New World, on the condition that the natives be converted to Christianity. Soon after, however, Spain and Portugal negotiated the Treaty of Tordesillas, settling Portuguese claims over modern-day Brazil.

More broadly, the Doctrine of Discovery shaped European kingdoms’ approach to colonizing the Americas, Asia and Africa. It was, simply put, the legal foundation of their claims over non-Christian peoples and territories.

Three centuries later, the Supreme Court of the newly independent United States cited the doctrine in a significant decision, Johnson v. McIntosh. According to this 1823 ruling, Indigenous peoples had no permanent right to the territory they lived on.

Despite forced Christianization, church leaders repeatedly despaired that Indigenous Latin Americans had not fully become Catholic. The Spanish reluctantly tolerated Indigenous Catholic practices, such as worshipping the Virgin of Guadalupe, an apparition of Mary in Mexico, and associating her with the Nahuátl mother goddess, Tonantzin. They reasoned that the Indigenous were novice Christians who would learn in time – an attitude that persisted for centuries.

The Catholic Church addressed multicultural questions in the 1960s, during the Second Vatican Council. Over four years, in thousands of hours of meetings and consultations, the church embarked on its first major reforms in centuries.

...continued

Comments