What really started the American Civil War?

Published in News & Features

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

What really started the Civil War? – Abbey, age 7, Stone Ridge, New York

The U.S. citizenship test – which immigrants must pass before becoming citizens of the United States – has this question: “Name one problem that led to the Civil War.” It lists three possible correct answers: “slavery,” “economic reasons” and “states’ rights.”

But as a historian and professor who studies slavery, Southern history and the American Civil War, I know there’s really only one correct answer: slavery.

White Southerners left the Union to establish a slave-holding republic; they were dedicated to the preservation of slavery.

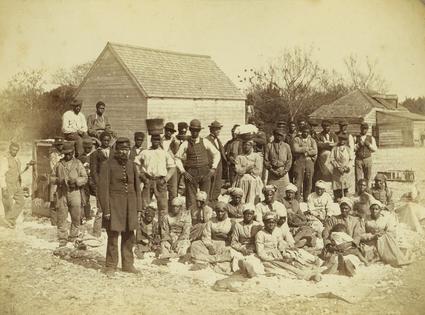

What’s more, unlike slavery in the ancient world, slavery in the United States was based on race. By the time of the Civil War, Black people were the ones enslaved; white people were not.

Every American citizen, whether born in this country or naturalized, should understand that the conflict over slavery is what caused the Civil War.

Slavery in the U.S. began at least as early as 1619, when a Portuguese ship brought about 20 enslaved African people to present-day Virginia. It grew so quickly that by the time Colonists fought for their independence from England in 1775, slavery was legal in all 13 Colonies.

As the 19th century progressed, Northern Colonies slowly abolished slavery; but Southern Colonies made it central to their economy. By 1860, nearly 4 million enslaved people lived in the South.

Increasingly, the North and South were at odds over the future of slavery. White Southerners believed slavery had to expand into new territories or it would die. In 1845, they pressured the federal government to annex Texas, where slavery was legal. They also supported an effort to purchase Cuba and add it as a slave state.

In the North, people generally opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories, and many favored the gradual emancipation of enslaved people. A smaller group, known as abolitionists, wanted slavery to end immediately.

But even though many Northerners opposed the expansion of slavery, they did not favor equal rights for Black people. In most Northern states, segregation was rampant, Blacks were barred from voting and violence against them was common.

By the 1850s, it became more difficult for the federal government to satisfy either side. The Compromise of 1850, a series of bills that tried to solve the problem, pleased almost no one.

The publication of the 1852 novel “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” – about the pain and injustice inflicted on an enslaved man – turned Northerners against slavery even more. In the 1857 Dred Scott decision, the Supreme Court ruled that enslaved people were not U.S. citizens, nor could Congress ban slavery in a federal territory. Two years later, the abolitionist John Brown attacked a federal arsenal in Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in an unsuccessful attempt to supply weapons to enslaved people.

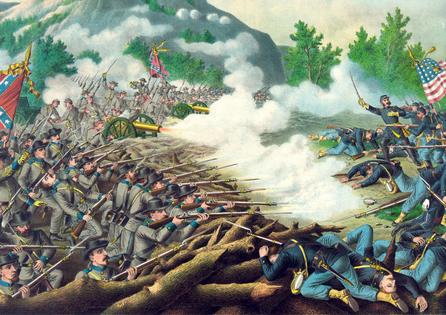

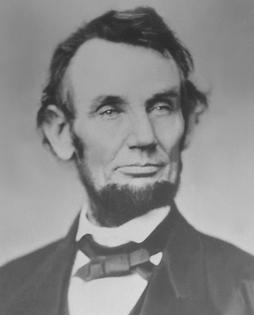

Amid this swirl of troubles, the presidential election of 1860 took place. A new political party, the Republican Party, was opposed to the spread of slavery throughout the western territories. With four major candidates running for president, Abraham Lincoln won the electoral vote – but only 40% of the popular vote.

The election of a president from a party that opposed slavery jolted white Southerners to action. Less than two months after Lincoln won, South Carolina delegates, meeting in Charleston, decided to secede from the Union – that is, to formally withdraw membership in the United States.

Other Southern states followed and said slavery was the primary reason for secession. Texas delegates wrote the abolition of slavery “would bring inevitable calamities upon both races and desolation” in the slave states. The Mississippi secession document said “our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery – the greatest material interest in the world.”

The vice president of the Confederacy, Alexander Stephens, also said slavery was the reason for secession, and that Thomas Jefferson’s words in the Declaration of Independence – that all men are created equal – were wrong.

“Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea,” Stephens told a crowd. “Its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.”

Although the evidence shows slavery caused the Civil War, some Southerners created a myth – the “Lost Cause” – that transformed Confederate generals into heroes who were defending freedom. To some degree, that myth has, unfortunately, taken hold. Some schools are still named after Confederate generals; so are some military bases, although that is changing.

It’s important to know the real reason for the Civil War so the country no longer celebrates historical figures who fought to establish a slave-holding republic.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. The Conversation is trustworthy news from experts, from an independent nonprofit. Try our free newsletters.

Read more:

The Confederate battle flag, which rioters flew inside the US Capitol, has long been a symbol of white insurrection

American slavery: Separating fact from myth

Robert Gudmestad does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments