White Lotus Day celebrates the 'founding mother of occult in America,' Helena Petrovna Blavatsky

Published in News & Features

Every May 8, thousands of people celebrate White Lotus Day, commemorating a remarkable and controversial Russian American woman: spiritual leader Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, who died in 1891.

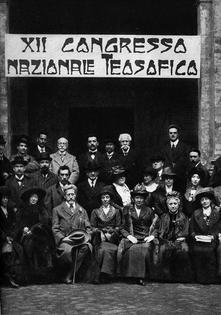

HPB, as followers affectionately call her, is remembered as a co-founder of the Theosophical Society. Aiming to create a universal brotherhood of humanity, theosophy claimed that its tenets came from spiritual masters in the Himalayas.

Today, the movement has over 25,000 official members, with more than 1,000 lodges and centers around the world. Other theosophical organizations, like United Lodge of Theosophists, also boast a robust official and unofficial membership that is harder to estimate.

Theosophy’s strongest influence, however, was on the esoteric spiritual revival that took Europe and the United States by storm in the late 19th century, with Blavatsky herself sometimes called “the mother of modern spirituality.” Her descriptions of Hinduism and Buddhism were often romanticized and inaccurate but fueled Western interest in Asian religions and gave rise to dozens of spiritual movements.

Blavatsky was born into a noble family in the Russian Empire, within the territory of modern Ukraine. As a child, she read occult literature at her grandfather’s home, sparking a lifelong desire to unlock secrets of the universe.

At 18, she escaped an unhappy marriage by secretly embarking on a British ship heading to Constantinople and for the next 25 years traveled the world in search of transcendental truth. Little reliable information about this period of her life survives, but Blavatsky’s “veiled years” seem to have included extensive travel on five continents and apprenticeships with various occult practitioners.

According to Blavatsky, during that time she came into contact with spiritual gurus named Morya and Koot Hoomi, whom she called her “ascended teachers.” Some scholars believe that these men never existed and were merely ruses HPB employed to garner support for her ideas. Most theosophists, however, maintain that these mahatmas – a term of respect in India – were real, and their teachings continue to be an integral part of theosophy.

In 1880, Blavatsky and her close companion Col. Henry Steel Olcott officially took pansil, or the five Buddhist vows, becoming among the first Westerners to do so publicly. Together with other leaders who later joined the theosophical movement, they popularized Buddhist and Hindu ideas in the West, introducing concepts such as karma and reincarnation.

Blavatsky poured ideas about spirituality into her written work, including classics of esoteric literature such as “Isis Unveiled,” “The Secret Doctrine” and “The Voice of the Silence.” Core tenets of her philosophy are summed up in “The Key to Theosophy,” which she wrote in 1889.

Adapting ideas from ancient Greek and Hindu philosophies, as well as Buddhism, theosophy teaches that the universe emanated from an impersonal divine absolute. All objects, animate and inanimate, share the same essence, and the goal of human evolution is spiritual liberation, which might be attainable after many reincarnations.

Styling itself as a universal “wisdom religion,” theosophy aimed to merge knowledge from philosophy, religion and science to explain secret laws governing the universe. Several of its leaders believed they possessed the ability to travel into a spiritual realm and access “Akashic records,” a repository of events and knowledge across time, and that they were in direct telepathic communication with the “ascended teachers.”

With other associates, Blavatsky in 1875 founded the Theosophical Society in New York, which boasted over 40,000 official members at the height of its popularity in the early 20th century. The society was set up like a philosophical discussion club, and today most of its public events explore the writings of Blavatsky and other theosophists, in addition to various religious traditions and concepts.

Ideologically, theosophy promoted the idea of radical egalitarianism among people of different races, beliefs and genders. To this day, the society’s official motto is “No Religion Higher Than Truth,” and the main objectives are “to form a nucleus of the universal brotherhood of humanity,” to “encourage the comparative study of religion, philosophy, and science,” and to “investigate unexplained laws of nature and the powers latent in humanity,” according to the Theosophical Society in America.

During Blavatsky’s era, Americans and Europeans were growing increasingly dissatisfied with traditional religions, especially Christianity. Termed the “Age of Doubt” by Victorian scholar Christopher Lane, the period was characterized by a widespread crisis of faith, brought about in part by advances in science and technology that challenged traditional worldviews.

In search of other spiritual ideas, some people started exploring occultism and spiritualism, practices that centered around the possibility of communication with the dead, while many turned to other cultures for inspiration. English translations of ancient Indian texts and popular books about Buddhism fostered such interest and created fertile ground for theosophy to gain popularity in the West.

Blavatsky’s India-based journal The Theosophist sought to foreground the work of her South Asian colleagues. Overall, however, she presented a romanticized vision of India, portraying its culture as a repository of “ancient wisdom,” in contrast to Western cultures she viewed as rationalist and dogmatic. Her descriptions paint an idealized picture of religious and philosophical traditions she portrayed as superior to materialistic Western modernity. In some ways, these ideas echoed common stereotypes in “Orientalist” art and writing of the era, which often depicted Asian cultures as unchanging and exotic.

Yet her claims that she was describing the “true” India shaped popular perceptions in the United States, Europe and Russia, as my current research shows. As a cultural historian who focuses on how religious ideas travel across the world and transform cultures, I am especially interested in how she sought to “translate” spiritual ideas for her Western audiences.

Blavatsky was not the first European scholar to turn to the East in search of ancient truth. Unlike many other scholars of India in the 19th century, however, she spent considerable time there, and in her writings from that period she often expresses outrage at British colonial injustices. In fact, after she moved the official headquarters of the Theosophical Society to Adyar, India, in 1879, Blavatsky was under surveillance by British authorities, who suspected that she was carrying out espionage for the Russians amid intense rivalry between the two empires.

But her legacy is complex. On the one hand, she can be thought of as an anti-colonial writer whose incriminating portrayals of brutality and excess in her travelogue “From the Caves and Jungles of Hindostan” were among the most scathing indictments of British colonialism at the time. On the other hand, Blavatsky failed to condemn Russia’s own imperial practices in Central Asia.

It is Blavatsky’s role in popularizing Eastern spiritual traditions abroad that has been her most lasting impact – even if her ideas were often unorthodox. Intellectual leaders from psychologist William James and Indian independence activist Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi to playwright George Bernard Shaw and inventor Thomas Edison were all members of the Theosophical Society or incorporated theosophical ideas into their work.

Theosophy now competes with other new religious movements for membership – but they, too, have been shaped by the woman writer Kurt Vonnegut called the “founding mother of occult in America.”

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. The Conversation has a variety of fascinating free newsletters.

Read more:

Why a 14th-century mystic appeals to today’s ‘spiritual but not religious’ Americans

How the image of a besieged and victimized Russia came to be so ingrained in the country’s psyche

Marina Alexandrova does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments