A brief history of the Black church's diversity, and its vital role in American political history

Published in News & Features

With religious affiliation on the decline, continuing racism and increasing income inequality, some scholars and activists are soul-searching about the Black church’s role in today’s United States.

For instance, on April 20, 2010, an African American Studies professor at Princeton, Eddie S. Glaude, sparked an online debate by provocatively declaring that, despite the existence of many African American churches, “the Black Church, as we’ve known it or imagined it, is dead.” As he argued, the image of the Black church as a center for Black life and as a beacon of social and moral transformation had disappeared.

Scholars of African American religion responded to Glaude by stating that the image of the Black church as the moral conscience of the United States has always been a complicated matter. As historian Anthea Butler argued, “The Black Church may be dead in its incarnation as agent of change, but as the imagined home of all things black and Christian, it is alive and well.”

As a scholar of Christian theology and African American religion, I’m aware of this long history of the Black church and its contribution to American politics. Its story began in the 15th and 16th centuries, when European empires authorized the capture, auction and enslavement of various peoples from across the coast of Western and Central Africa.

As millions were transported through the “Middle Passage” to the Americas, Europeans forcefully baptized the enslaved into the Christian faith despite many of them adhering to traditional African religious systems and Islam. European slave traders dismissed Africans as “heathenish” to justify their enslavement of Africans and the coercive proselytization to Christianity.

In the 1600s, British missionaries traveled throughout the American Colonies to convert enslaved Africans and the Indigenous peoples of the continent. Originally, however, white slaveholders were hesitant to convert enslaved Africans to Christianity because they feared that Christian baptism would lead to the enslaved Africans’ freedom, causing both economic ruin and social upheaval. They widely supposed that British laws mandated the freedom of all baptized Christians, and thus white slaveholders initially refused to grant missionaries permission to instruct enslaved Africans into the Christian faith.

By 1706, six Colonies had passed laws that declared that Africans’ Christian status did not alter their social condition as slaves. Consequently, missionaries created “slave catechisms,” modified religious instruction manuals that instructed enslaved Africans about Christianity while reinforcing their enslavement.

Over time, evangelical Protestant groups followed suit in their proselytization of the enslaved community, most notably during the First and Second Great Awakenings, the Protestant religious revivals that swept across the American nation in the mid-18th and early 19th centuries.

Both during and after the end of slavery, African Americans began to establish their own congregations, parishes, fellowships, associations and later denominations. Black Baptists founded first the National Baptist Convention USA, in 1895, the largest Black Protestant denomination in the United States. The National Baptist Convention of America International and the Progressive National Baptist Convention were founded years later.

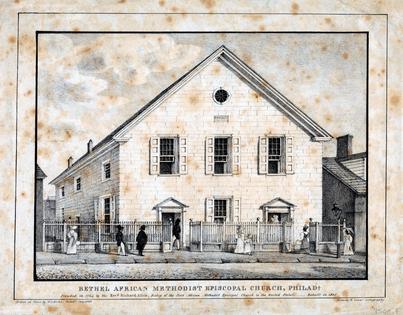

The first independent Black denomination, the African Methodist Episcopal Church, which was formalized in 1816, grew out of the Free African Society founded by Richard Allen, a former enslaved man and Methodist minister, in the city of Philadelphia in 1787. Allen and his colleague Absalom Jones walked out of St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church after white members demanded that Allen and Jones, who had been kneeling in prayer, leave the ground floor and go to the upper balcony, which was designated for Black worshippers.

...continued

Comments