Business

/ArcaMax

Wells Fargo moves to settle DEI lawsuit over claims it held phony job interviews

Wells Fargo and its shareholders agreed to settle a federal class-action lawsuit alleging the bank misrepresented its diversity, equity, and inclusion hiring initiatives by holding phony job interviews.

Terms of the settlement are being negotiated and expected to be submitted for court approval by Oct. 13, according to a Sept. 15 filing in U.S....Read more

Universal Orlando guest dies after riding Epic Universe's Stardust Racers

ORLANDO, Florida — A man in his 30s who became unresponsive after riding the Stardust Racers thrill ride at Universal Orlando’s new Epic Universe theme park has died, according to park officials and police.

A statement from Universal said the man had been at the park Wednesday night and fell ill after riding the twin coaster attraction ...Read more

Real estate Q&A: Should I take HOA to small claims court over landscaping demand?

Q: We live in a gated community with an HOA and had our landscaping plan approved by the Architectural Review Committee in 2015. This plan included adding shrubbery and rocks around a roadside tree. Recently, the HOA management stated that this area is community property, and the landscaping violates community rules, demanding its removal at our...Read more

'Bringing us into the future': An independent architect's thoughts on San Diego airport's new Terminal 1

To the naked eye, it is hard not to marvel at the new Terminal 1 at the San Diego International Airport in comparison to its predecessor, but how experts view it might be different than the average Joe.

The public was recently offered their first view of the terminal ahead of its opening next week. Daniela Deutsch, the dean of architecture at ...Read more

Loyola Marymount abruptly rescinds recognition of faculty union after months of negotiation

LOS ANGELES — After 10 months of negotiations, Loyola Marymount University abruptly announced it would no longer recognize its faculty union.

The news, delivered in an email to students and employees on Friday, sent shock waves through the union, which represents nearly 400 part-time and full-time educators who do not hold tenure-track ...Read more

Amazon bumps pay, lowers health insurance costs for warehouse workers

Amazon says it will spend more than $1 billion to raise pay and lower health insurance costs for warehouse and transportation employees in the U.S.

The company said Wednesday that the average pay for a worker in Amazon's vast logistics empire will increase to $23 an hour this year. The average total compensation, including benefits, will pencil...Read more

Holiday spending to dip this season, upping competition for retailers

Consumers plan to cut holiday spending this year, putting extra pressure on Twin Cities retailers for their critical shopping season.

Shoppers will shrink their holiday budgets by an average of 5%, the first notable decline since 2020, according to PwC’s annual Holiday Outlook survey. That decline five years ago occurred amid the pandemic and...Read more

5 things to know about Baltimore's grants to revive vacant properties

Baltimore is aiming to reduce its thousands of vacant properties by offering grant funds to those who are interested in fixing them up.

Mayor Brandon Scott, a Democrat, announced the “first round” of City-Wide Affordable Housing TIF Funds last week. The initiative is part of a $3 billion plan over 15 years from the two-term mayor that aims ...Read more

Amazon pledged to support affordable housing. How has it fared so far?

It's a sunny, September day in SeaTac, Washington, and three kids are playing in the courtyard of Connection Angle Lake, a new 130-unit affordable housing project roughly 50 feet from the last stop on Sound Transit's 1 Line.

Inside, the studios, one-bedroom and multi-bedroom apartments look fresh with stainless steel appliances and views that ...Read more

Gurnee Mills announces new slate of businesses: 'The death of malls is vastly overrated'

GURNEE, Illinois — Gurnee Mills, a mall located in a northern exurb of Chicago, recently announced a new slate of stores and businesses coming to the mall in the near future, a sign of its “thriving” health, according to shopping center representatives.

It’s a far cry from reports that came out about the mall leading up to the pandemic,...Read more

Bank of America hourly workers see pay raise again, final step of long-term plan

Bank of America is raising its minimum hourly wage to $25 starting in October, the Charlotte, North Carolina-based banking giant announced Wednesday.

All full-time and part-time hourly positions in the U.S. will see changes to their pay, according to the bank.

The minimum starting salary will help employees to build a long-term career at Bank ...Read more

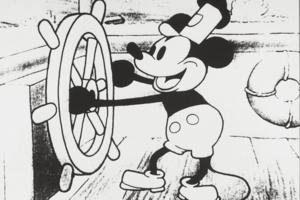

Law firm sues Disney over 'Steamboat Willie' ad

The Morgan & Morgan law firm sued Disney in federal court on Wednesday, seeking a ruling that it can use an adaptation of the nearly century-old “Steamboat Willie” cartoon in one of its ads without violating the entertainment giant’s intellectual property rights.

The iconic 1928 animated short, featuring the public debut of Mickey and ...Read more

General Mills zeroing in on 'value' to spur growth again

Chex Mix had a hit with a new package this summer, a big clear jar of the snack mix that boosted sales for the General Mills-owned brand.

“People love being able to see the product,” General Mills CEO Jeff Harmening said Wednesday on a call reporting the company’s earnings. “The product is at a pretty high price point, but the packaging...Read more

After Fed rate cut, Powell says jobs market no longer very solid

Federal Reserve officials lowered their benchmark interest rate by a quarter percentage point and penciled in two more reductions this year following months of intense pressure from the White House to slash borrowing costs.

Chair Jerome Powell pointed to growing signs of weakness in the labor market to explain why officials decided it was time ...Read more

After Fed rate cut, Powell says jobs market no longer very solid

Federal Reserve officials lowered their benchmark interest rate by a quarter percentage point and penciled in two more reductions this year following months of intense pressure from the White House to slash borrowing costs.

Chair Jerome Powell pointed to growing signs of weakness in the labor market to explain why officials decided it was time ...Read more

Fed cuts rates quarter point, signals labor market concerns

Federal Reserve officials lowered their benchmark interest rate by a quarter percentage point and penciled in two more reductions this year following months of intense pressure from the White House to slash borrowing costs.

In their post-meeting statement, policymakers pointed to growing signs of weakness in the labor market to justify their ...Read more

The Fed just lowered interest rates. What does that mean to California?

For the first time in nine months, the Federal Reserve on Wednesday lowered its key interest rate, a quarter-percentage point cut likely to only slightly lower borrowing costs for consumers buying items big and small.

“Rate cuts are welcome news for Americans with debt, but one small reduction won’t make much difference when bills come due,...Read more

Gen Z leads biggest drop in FICO scores since financial crisis

Gen Z borrowers took the biggest hit of any age group this year, helping pull overall credit scores lower in the worst year for U.S. consumer credit quality since the global financial crisis roiled the world’s economy.

The average FICO score slipped to 715 in April from 717 a year earlier, marking the second consecutive year-over-year drop, ...Read more

'The news devastated me': Pennsylvania NPR station will be first in the US to go dark following Trump's cuts

A public media organization in a university town just a few hours northwest of Philadelphia is set to be the first in the country to go dark after the Trump administration stripped away federal funding for NPR and PBS.

WPSU, Penn State’s NPR and PBS affiliate and the first educational TV station in Pennsylvania, will go dark sometime within ...Read more

Target debuts thousands of holiday gifts, plus weekly sales and faster delivery

Halloween merchandise hit some stores before the Fourth of July, and Thanksgiving items were in already stores in August.

Given that it’s mid-September, retailers are rolling out products for the next winter big holiday: Christmas.

On Tuesday, Target launched a four-pronged approach to its holiday shopping experience.

Prong one: new items. ...Read more

Popular Stories

- Law firm sues Disney over 'Steamboat Willie' ad

- Bank of America hourly workers see pay raise again, final step of long-term plan

- After Fed rate cut, Powell says jobs market no longer very solid

- 'The news devastated me': Pennsylvania NPR station will be first in the US to go dark following Trump's cuts

- One of the country's most distinctive car collections goes on sale in Chicago