More climate-warming methane leaks into the atmosphere than ever gets reported – here’s how satellites can find the leaks and avoid wasting a valuable resource

Published in Science & Technology News

Far more methane, a potent greenhouse gas, is being released from landfills and oil and gas operations around the world than governments realized, recent airborne and satellite surveys show. That’s a problem for the climate as well as human health. It’s also why the U.S. government has been tightening regulations on methane leaks and wasteful venting, most recently from oil and gas wells on public lands.

The good news is that many of those leaks can be fixed – if they’re spotted quickly.

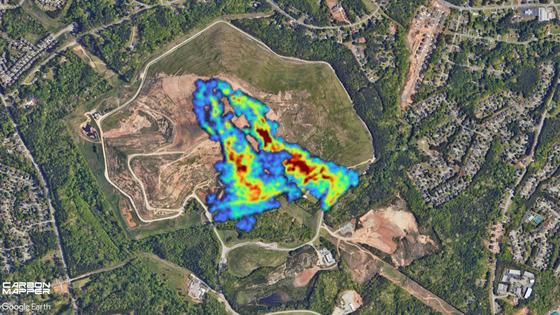

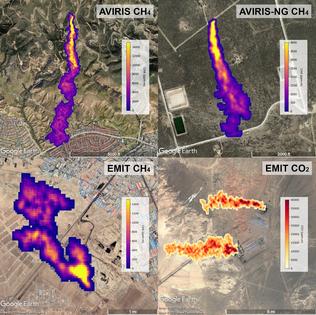

Riley Duren, a research scientist at the University of Arizona and former NASA engineer and scientist, leads Carbon Mapper, a nonprofit that is planning a constellation of methane-monitoring satellites. Its first satellite, a partnership with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the Earth-imaging company Planet Labs, launches in 2024.

Duren explained how new satellites are changing companies’ and governments’ ability to find and stop methane leaks and avoid wasting a valuable product.

Methane is the second-most common global-warming pollutant after carbon dioxide. It doesn’t stay in the atmosphere as long – only about a decade compared to centuries for carbon dioxide – but it packs an outsized punch.

Methane’s ability to warm the planet is nearly 30 times greater than carbon dioxide’s over 100 years, and more than 80 times over 20 years. You can think of methane as being a very effective blanket that traps heat in the atmosphere, warming the planet.

What worries many communities is that methane is also a health problem. It is a precursor to ozone, which can worsen asthma, bronchitis and other lung problems. And in some cases, methane emissions are accompanied by other harmful pollutants, like benzene, a carcinogen.

In many oil and gas fields, less than 80% of gas that comes out of the ground from a well is methane – the rest can be hazardous air pollutants that you wouldn’t want anywhere near your home or school. Yet until recently, there was very little direct monitoring to find leaks and stop them.

In its natural form, methane is invisible and odorless. You probably wouldn’t know there was a massive methane plume next door if you didn’t have special instruments to detect it.

Companies have traditionally accounted for methane emissions using a 19th-century method called an inventory. Inventories calculate emissions based on reported production at oil and gas wells or the amount of trash going into a landfill, where organic waste generates methane as it decomposes. There is a lot of room for error in this assumption-based accounting; for example, it does not account for unknown leaks or persistent venting.

...continued

Comments